Owning My Carbs and Being Honest with Myself

By Cherise Shockley

By Cherise Shockley

I learned that I wasn’t counting carbs as accurately as I thought – which led me to investigate glass ceilings and why carb counting can be so hard for people with diabetes.

The newest chapter of my carb journey started during an appointment with my endocrinologist last year. I had received Tandem’s Control-IQ pump at the end of the summer, and I was embracing the benefits of the technology to help my diabetes management. Luckily, I had an appointment scheduled with Dr. P. just a month after being on the new pump. I was planning to discuss my switch from Loop to Control-IQ, as well as the post-meal glucose spikes that seemed to linger and result in me crashing later. I did not want to focus on my A1C – I knew it would be higher than usual due to stress.

On the day of the appointment, we spent two minutes talking about my A1C – it was higher than the last time we met. Dr. P then took my continuous glucose monitor (CGM) reports from the past two weeks and laid them out on the exam table so that we could talk about each time I was out of range.

Dr. P asked, “Are you entering the correct number of carbs in your pump? Your pump settings look great.” I thought about his questions before I responded, “Yes, I enter the correct amount of carbs, but sometimes I guess.” Dr. P continued to comb through my data, found a day that I was 90% in range, and asked what I did. I had cycled for 30 minutes and remembered to pre-bolus before I ate – which doesn’t always happen. Dr. P told me to focus on pre-bolusing to help with the post-meal spike.

I left Dr. P’s office determined to pre-bolus before meals. But as I began my new mission, I noticed that even with the pre-bolus, I still had lingering spikes and lows. I changed my insulin sensitivity to decrease the lows, but I could not figure out why I continued to experience highs.

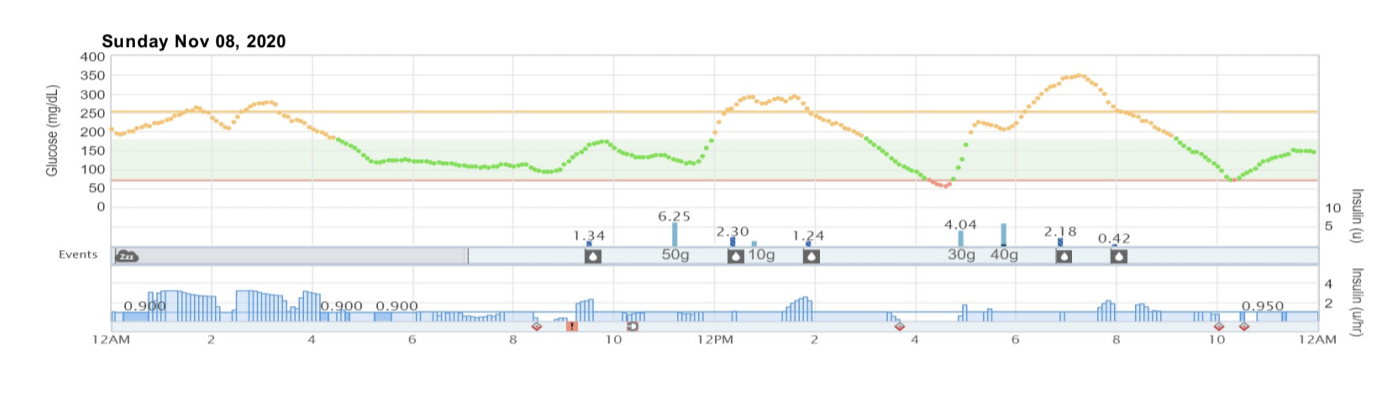

So, I went back to the drawing board. I tracked what I ate, counted the number of carbs, and entered it in the pump. Unfortunately, I did not see the improvements I was looking for. I reached out to my friend Natalie, who has type 1 diabetes and is a Nurse Practitioner, to talk about my Control-IQ experience. I told her about the post-meal spikes, and when she asked about my pump settings, I shared my Control-IQ reports with her (see below for an example). After looking at the data for less than five minutes, she asked, “Are you entering the correct number of carbs?” I told her I thought so. Natalie wasn’t so sure, “You eat 35, 25, 45 grams of carbs at each meal? What did you eat on Sunday? Your blood sugar went up to 250 mg/dl and stayed high for a long time.”

That was my moment of truth. I told Natalie I ate my favorite chocolate chunk cookie that day. She asked me how many carbs the cookie contained, and I told her 68 grams; she wondered why I only bolused for 55 grams. I paused before I replied – I did not know the answer.

Natalie then asked me if I had a glass ceiling for entering carbs in my pump. She explained that this means even though I know I eat 63 carbs, I will only enter 50 carbs in my pump because anything higher than that concerns me. What she said was interesting; I had never heard anyone describe it to me in that way.

I turned to social media to ask my friends with diabetes how they would rate their carb counting skills – what did they struggle with the most? Do they find it challenging to share the number of carbs they actually eat with their healthcare professional? The responses were so interesting that I might have to write another article to share their replies. The comment that I could best relate to was from Theresa Hastings. She was taught strict carb counting early on because she was on both regular and NPH insulins. Her meals could not be more than 60 grams of carbs, and snacks could not be more than 15 grams of carbs. Twenty-two years later, she struggles with entering carb counts greater than those numbers even when she knows the carb count is higher. Our experiences were similar, though when I was diagnosed, I was put on oral treatments instead of insulin. I was taught to eat no more than 30 to 40 grams of carbs per meal and no more than 15 grams of carbs for snacks. My personal glass ceiling seemed to be 45 grams, and anything above that I would just correct later.

To learn more about carbohydrate glass ceilings and why some people have one, I talked to Dr. Korey Hood, a professor of pediatric endocrinology and psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University who has lived with type 1 diabetes for over 20 years. Dr. Hood told me that all parts of diabetes management can be challenging, and carb counting is particularly tough because it is hard to be accurate and precise. He always recommends people with diabetes meet annually with their diabetes educator (CDCES) to get a refresher on different aspects of diabetes management, including carb counting.

Dr. Hood said that the glass ceiling is most likely due to one of two issues – worries about hypoglycemia or the meaning behind taking such a big dose of insulin. Dr. Hood said that “many of us with diabetes, particularly those on insulin, worry about going low. Why wouldn’t we – it is a terrible feeling! We often experience fears of hypoglycemia because we had a terrible low in the past and have a desperate desire to avoid it in the future. When we worry about hypoglycemia, we scale back our insulin dosing. This prevents the low but also likely results in high glucose levels. So, it really is not a good strategy.”

Dr. Hood said that to overcome the fear of hypoglycemia, people have to increase their confidence in preventing lows and in their ability to treat them effectively. He said that this can be done with the help of mental health support and by reviewing available information online. One helpful resource is diaTribe’s “Hypoglycemia Preparedness: How to Know Before You Go Low.”

To Dr. Hood, the second issue is that “when we increase insulin doses and need larger amounts, we can think this means that our diabetes is getting worse. Or that we’ve done something wrong. The reality is that rates and amounts will vary considerably over time. They can be different within days, weeks, or months. Taking more insulin does not mean you failed or that your diabetes is getting worse. It just means you need more insulin!”

Writing this article has been therapeutic, and it let me know that I am not alone. Do I need a chocolate chunk cookie several times a week? For me, the answer is no – but I will still probably eat one once a week. Entering the correct number of carbs, no matter the amount, doesn’t mean I am breaking the rules or that I will be judged; however, technology is only as good as the information I put into it. Bolusing correctly should allow the technology to do its job effectively. If I happen to go low, the closed loop technology can handle it, and so can my family if I need their help. The graph below shows what happens now when I enter the correct number of carbs and pre-bolus for a meal.

Being honest with myself will also allow Dr. P to do his job effectively. Dr. P has never judged me or scolded me for high A1C tests or anything else for that matter. By being honest with him, he can do his job better and help me manage my diabetes.

I know my carb counting skills will never be perfect. Eating low-carb every single day does not work for me – and I am okay with that. I’ve realized that a carb-counting refresher will be helpful for me at least once or twice a year, and ever since learning about my own carb glass ceiling, I’ve made some changes. With routine exercise, meditation, dusting off old apps like MyFitness Pal and Calorie King, and using new tools like Spark Recipes, I have reduced the number of carbs I eat by half. By pre-bolusing before meals when I can, my average Time in Range has gone from 77% to 80% – and though this may not be a massive difference by clinical standards, it’s a major personal win!

This article is part of a series on time in range.

The diaTribe Foundation, in concert with the Time in Range Coalition, is committed to helping people with diabetes and their caregivers understand time in range to maximize patients' health. Learn more about the Time in Range Coalition here.