How I Loop: Two Years Using An iPhone App To Automate My Insulin Delivery

By Adam Brown

By Adam Brown

By Adam Brown

Read about Adam’s time-in-range over two years on Loop – +2 hours/day! – along with quality of life changes, better sleep, and the mealtime impact. Part 1 of a series on what it’s like to use a hybrid closed loop app to automate basal insulin delivery.

Adam: “Honey, Loop, doesn’t seem to be working, so I won’t have it running tonight.”

Priscilla: “Really?”

Adam: “Yes.”

Priscilla: “Oh gosh, that is terrible news.”

For the past two years, I’ve been wearing a do-it-yourself automated insulin delivery system called “Loop,” and I’ve looked at 40 months of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) data to truly examine its impact. Over 730 days of using Loop, I have spent two more hours per day in the range of 70-140 mg/dl – that’s an extra one full month per year in-range. Alongside that huge gain has come much better sleep, less diabetes burden, a happier girlfriend, and greater overnight safety.

This will be a multi-part series on Loop, as we hope to publish a variety of views – adults, children, parents, different ages, newly diagnosed, etc. An explanation of the system is below, followed by my experience. We’ll publish Kelly’s experience soon after this one. If you’d like to share your story, view the instructions here!

What is Automated Insulin Delivery? What is Loop? Why do they matter?

What is Automated Insulin Delivery? What is Loop? Why do they matter?

Automated insulin delivery systems (aka “closed loop”) are one of the most exciting advances in diabetes technology, since they reliably improve time-in-range (especially overnight), reduce high and low blood sugars, reduce time spent on diabetes, and free up mental space.

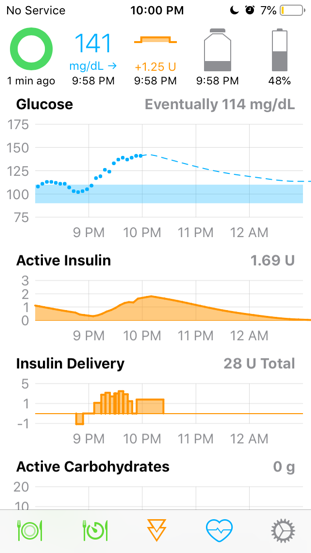

Loop is a flavor of automated insulin delivery that is open-source and do-it-yourself (DIY). The Loop app runs on an iPhone and receives CGM values every five minutes from compatible Dexcom or Medtronic CGMs. The app communicates with a small bridging device called a RileyLink (white box in picture above), which allows the phone to communicate with old Medtronic pumps. The Loop app takes the CGM values, runs them through an algorithm, and automatically adjusts basal insulin delivery on the pump.

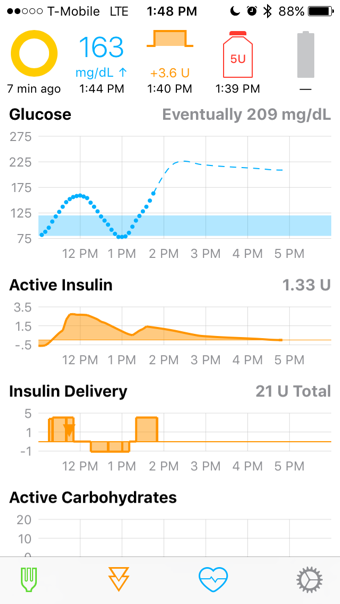

Loop aims to minimize low and high blood sugars and target a customizable glucose value or range. As my blood sugar trends above target, Loop delivers more basal insulin (see picture at right). As it trends down, it reduces or suspends insulin. Currently, my Loop system is set to target 100 mg/dl and is configured to deliver up to 4.5 units per hour of basal insulin, which is between 4-5 times my normal basal rate.

Loop aims to minimize low and high blood sugars and target a customizable glucose value or range. As my blood sugar trends above target, Loop delivers more basal insulin (see picture at right). As it trends down, it reduces or suspends insulin. Currently, my Loop system is set to target 100 mg/dl and is configured to deliver up to 4.5 units per hour of basal insulin, which is between 4-5 times my normal basal rate.

Like the MiniMed 670G, Loop is a “hybrid closed loop,” meaning it only adjusts basal insulin and cannot give automatic boluses. I tell the app when I’m about to eat, it recommends a bolus, and then I use a fingerprint to confirm the amount and send it to the pump. Loop also allows me to bolus from an Apple Watch without touching my pump or phone.

Loop is a do-it-yourself experimental app developed by people with diabetes and their loved ones who didn’t want to wait for device manufacturers and the FDA. The current “DIY” version described below is not FDA approved, uses old Medtronic pumps that are out-of-warranty, and requires some perseverance and troubleshooting to install and maintain. There are an estimated 1,000-1,500 DIY Loop users globally. You can read about setting up Loop here.

The non-profit Tidepool is working on a version of Loop that might obtain FDA approval in future. It would be available on the Apple app store and work with in-warranty, compatible insulin pumps; read our article here and see Tidepool’s website.

The MiniMed 670G is currently the only FDA-approved hybrid closed loop system in the US, though more are expected on the market in the next 2-3 years: Tandem’s Control-IQ (summer 2019), Bigfoot Loop (~2020), Lilly (~2019-2021), Insulet Horizon (~second-half of 2020), and Beta Bionics iLet (~second-half of 2020).

For now, I’m using the DIY Loop app because: (i) it is available today and the only other option is the 670G; (ii) it works well; and (iii) it is worth the risk and inconvenience to experience AID, because it is so great.

How I Loop

Looper Name: Adam Brown

-

Years with Diabetes: 17

-

Time wearing a DIY Closed Loop: 2 years

-

Current setup: Loop app running on iPhone 8, Dexcom G6 CGM, Medtronic Paradigm 522 Pump, Riley Link communication relay device

-

Coding experience: ZERO, but I was able to easily follow the instructions

Click to jump to a section:

-

How has wearing your DIY system changed your mealtime insulin dosing or approach?

-

If you could wave a magic wand, what is the #1 thing you would change about your DIY system?

-

What will it take for you to move from your DIY system to a commercial closed loop system?

-

What is the biggest public misunderstanding about DIY systems?

Q: How has wearing Loop changed your glucose levels?

I’ve looked as far back in time as my CGM data goes – 40 months in total – comparing 16 months of my own manual pump and CGM care (when I started wearing the Dexcom G5 for the first time) vs. 24 months of using Loop.

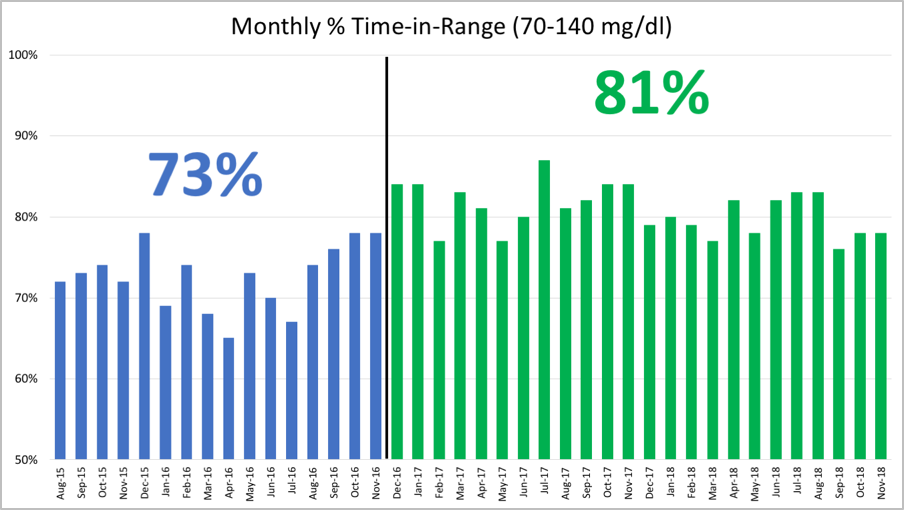

Overall, my time-in-range (70-140 mg/dl) has increased by an impressive 1.9 hours per day while on Loop – far more than I would have guessed. On average, my daily time-in-range was 73% over 16 months of manual care vs. 81% over the past 24 months on Loop. That may not seem like a large difference, but it’s actually massive: two hours per day equates to an extra one month per year in the range of 70-140 mg/dl.

Here is my monthly time-in-range charted over 40 months, separating 16 months of manual care on the left in blue vs. 24 months of Loop on the right in green. Over nearly 20,000 hours of use, Loop is consistently more effective and safer than my own manual insulin dosing.

My time in the wider range of 70-180 mg/dl has not meaningfully changed: 94% on manual care vs. 96% on Loop. This isn’t surprising, as food choices are the biggest driver of time in 70-180, and my eating approach has not changed. For me, the advantage of Loop has been increasing time in 70-140 mg/dl safely without causing more hypoglycemia. (On a related note, all the food-based CGM data in my book, Bright Spots & Landmines, was taken before using Loop.)

A skeptic would note that my glucose was already in range for most of the day prior to Loop, which is true. But diabetes is all about tradeoffs: Loop has further improved my time-in-range, reduced my diabetes hassle, improved my sleep, and added zero cost to my care (same pump and CGM supplies). That’s a slam dunk!

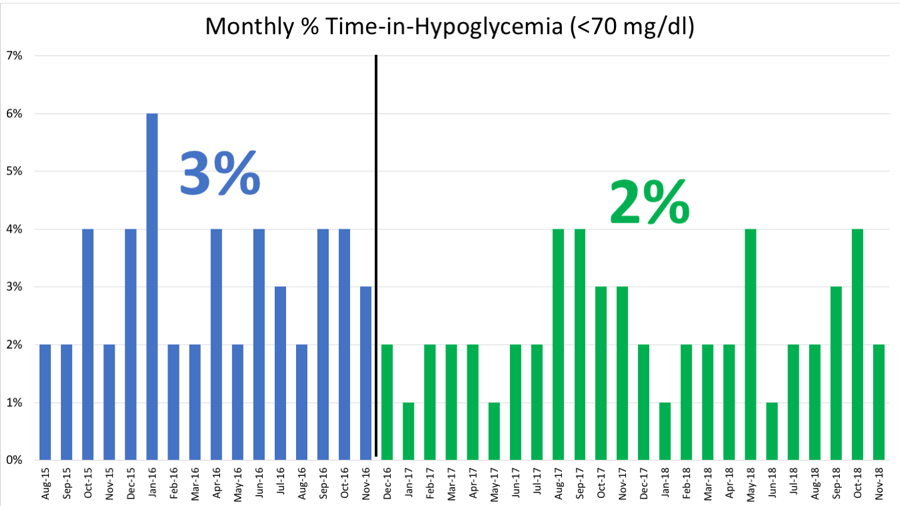

My time-in-hypoglycemia has declined by 12 minutes per day while on Loop. On average, my time less than 70 mg/dl was 3.1% on manual care vs. 2.3% on Loop. Again, that sounds small, but even minutes make a huge difference in diabetes. For instance, with 3% time in hypoglycemia on my own care, I had a subscription to get glucose tabs delivered to my house every couple of months – I burned through them treating lows all the time. On Loop, I’ve cancelled the subscription, since my lows are both less frequent and less severe.

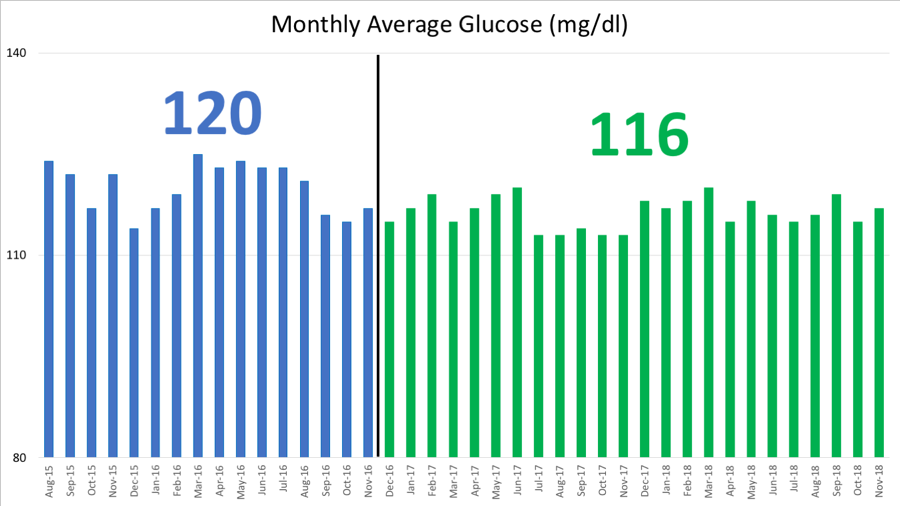

My average glucose has dropped by 5 mg/dl while on Loop: 120 mg/dl on manual care vs. 116 mg/dl on Loop.

Overnight

Most of all, I’ve loved using Loop overnight: I wake up nearly every morning at 90-120 mg/dl, which makes a tremendous difference for my quality of life (and those around me!), energy levels, mood, and blood sugars throughout the next day.

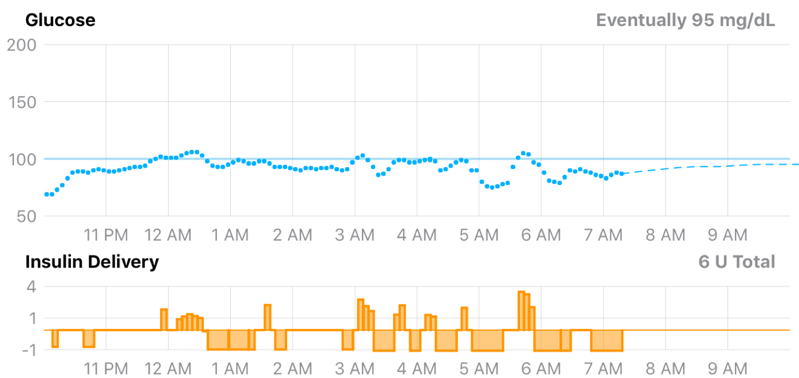

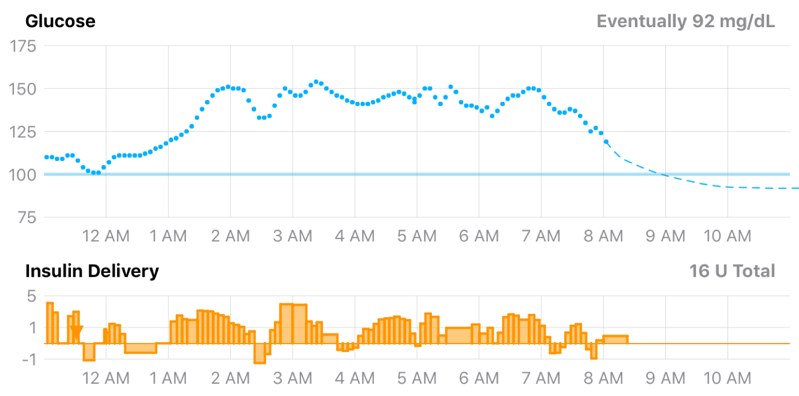

Here are two powerful example nights on Loop from a week ago – the first was an early dinner (~6:30 pm), while the next night had a late dinner (~9:30 pm). By morning on night one, Loop had delivered only 6 units of insulin; by morning on night two, it had given me 16 units! Without Loop, both nights would have had the exact same basal rate, meaning lows all night in the first example and highs all night in the second example.

1. Early Dinner

2. Late Dinner

I also feel much safer going to bed, particularly when I have a borderline low blood glucose (e.g., 78 mg/dl) or have exercised a lot – I know the system will take care of me, and I won’t wake up four times to treat a low, or have to deal with a high from overcorrecting right before bed.

My girlfriend, Priscilla, has also seen an improvement in her sleep. The conversation at the start of this article was an eye opener: I had little idea how much my manual diabetes care, filled with overnight CGM alarms and waking up, negatively impacted her sleep. A work colleague, Brian Levine, told me the same thing – sharing a hotel room with me while we are at conferences is now far less of an alarm burden with Loop.

It’s amazing how great technology can actually surface these issues, as neither Priscilla nor Brian had ever brought this up; they were just stuck with it, and were too polite to say anything. These quality-of-life improvements are harder to measure than blood sugar, but they are equally meaningful.

When you wear a closed-loop system, you realize just how insane the current standard of care is: using the same basal insulin dose every single night. In reality, insulin requirements are not constant from night to night – they can vary dramatically, as noted above and based on many factors. Closing the loop is a powerful solution to the overnight unpredictability most insulin users face.

Q: How has wearing your DIY system changed your mealtime insulin dosing or approach?

Loop is a “hybrid closed loop,” similar to Medtronic’s MiniMed 670G – it automates basal insulin delivery, but I’m responsible for mealtime bolus doses.

I’ve talked previously about the time-in-range benefits of eating fewer carbohydrates, which is the #1 reason why my time-in-range (70-140 mg/dl) was over 70% on my own care and over 80% on Loop. However, Loop does have some nice synergy with low-carb eating.

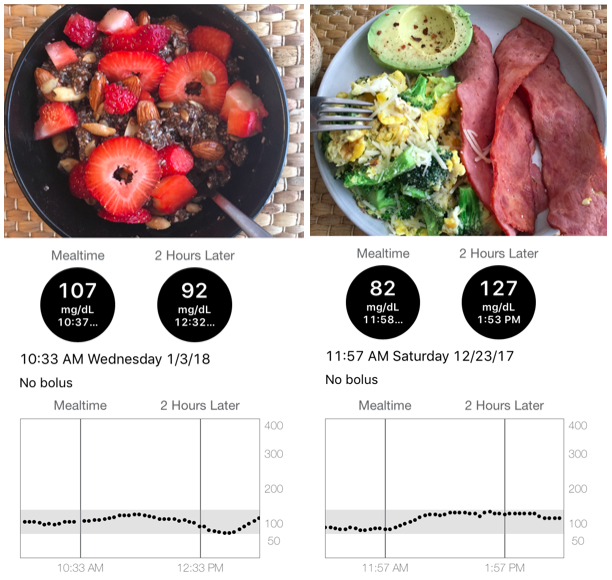

First, if I forget to take a bolus completely, Loop can handle a low-carb meal really well – once it sees a steady upward CGM trend, it will ramp basal insulin delivery to curb the high. That means I rarely go over 160 mg/dl with a missed bolus.

In other words, eating a low-carb/high-fat diet helps turn a hybrid closed-loop system into a near-fully closed-loop system that can handle meals on its own. This has dramatic implications for diabetes burden, missed boluses, and glucose outcomes. The pictures below are good examples of breakfast – Loop handled both without any intervention, keeping me in-range.

Another huge benefit of Loop is not feeling tethered to constantly eat. It is much safer to skip meals, which has allowed me to test out 16:8 intermittent fasting as another diabetes tool – that means I eat all my meals within an eight-hour window, which is usually 12 noon (eggs or chia pudding) until 8pm. Spacing out meals is another useful strategy for keeping blood sugars in range, and it is much safer to do so on Loop. (Disclaimer: This is not a recommendation for you to try intermittent fasting, as it can lead to lows – especially for insulin users. I’ll have a very in-depth pro/con column on intermittent fasting in 2019.)

There is a perception that a closed-loop system allows you to eat whatever you want. This is not true in my experience. Eating crazy meals results in crazy blood sugars, even with automated insulin delivery. Indeed, Loop cannot cover higher-carb meals on its own – without a bolus, blood sugar will go high and stay there for hours until Loop’s automated basal insulin delivery brings it back down.

Q: In what circumstances does Loop struggle to keep you in range? Are there times when you turn off closed loop?

Loop is not a perfect tool and can struggle in a variety of scenarios:

-

Rapid drops in blood sugar, especially endurance exercise

-

Rapid increases in blood sugar – e.g., higher-carb meals, high-intensity exercise, stress, caffeine

-

Manual human tinkering (impatience!) – e.g., adding a correction bolus to get back into range faster, over-treating a low with too much food

-

Inaccurate/unreliable CGM readings

Most of these issues are not specific to Loop, but relate to the lag time inherent in all automated insulin delivery systems –“rapid-acting” insulins take about 60-90 minutes to peak, meaning any change to insulin right now won’t impact my blood sugar for some time.

Let me give two examples:

1. Exercise

1. Exercise

On this particular morning, my blood sugar was floating in the 150-200 mg/dl range. Since Loop targets 100 mg/dl, it began delivering about 3-4x my basal rate in an attempt to bring me down to target. (In the picture on the right, note the tall orange bars under “Insulin Delivery,” which signify additional insulin delivery.) On that day, I decided to go for a bike ride to bring my blood sugar down, forgetting that Loop had given me extra insulin for over an hour. The rapid drop in blood sugar around 12 noon reflects cycling combined with all of the previously delivered extra basal insulin hitting my system. The result was a crash low, and then Loop suspended for an hour to bring me back into range. Extra basal insulin can be like a freight train, especially when combined with exercise.

Now before endurance exercise, I turn off Loop and use other strategies to handle blood sugars, such as consuming glucose tabs to get to my pre-exercise glucose target (+20 mg/dl per tab).

2. “Rollercoaster” – Low Then High

2. “Rollercoaster” – Low Then High

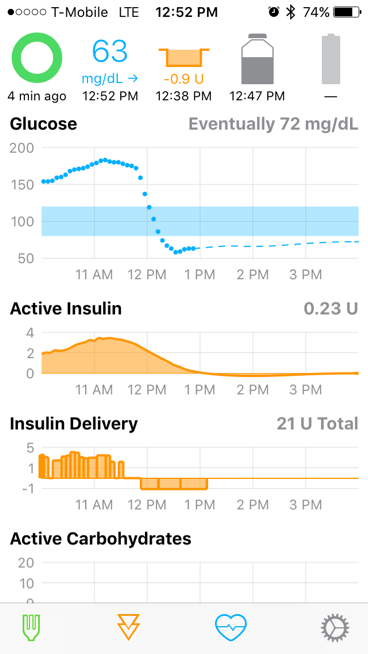

In this example, I woke up with a slightly low blood sugar around 70 mg/dl, and Loop had been suspended for a while in an attempt to avoid a more significant low.

Because I was hungry, I ate my usual low-carb breakfast (chia pudding), but forgot to “announce” it to Loop. Combined with the previously suspended insulin and caffeine, my blood sugar then rocketed up toward 175 mg/dl.

Loop responded quickly to the trend by increasing basal insulin delivery, which is shown in the tall orange blocks under “Insulin Delivery” – I was getting about 3-4x my normal basal rate at that time. I also noticed the upward trend and added a bolus on top of that (diamond triangle under insulin delivery).

I walked 20 minutes into work, and combined with the higher basal rate and my manual bolus tinkering, I crashed low.

I ate two glucose tabs to correct the low, forgetting that Loop had already been suspended for about an hour (12:15-1:15pm) based on the downward trend. That drove my blood sugar high and on a fairly aggressive upward trend.

This rollercoaster pattern was common in my early days of Loop. To avoid it, I try to: (i) not take manual correction boluses if Loop has already increased basal insulin; (ii) remember to announce meals to Loop if my blood sugar is low going into a meal; (iii) not overeat for low blood sugars; and (iv) not have Loop’s target set too aggressively (mine is now at 100 mg/dl; any lower was not safe for me).

I now take half my usual hypoglycemia correction carbs – meaning if I would normally eat two glucose tabs for a blood sugar of 60 mg/dl, now I only eat one.

Hybrid closed loop systems do have a learning curve: who is in charge and when? I initially tinkered too much with my insulin dosing during the day with Loop; this resulted in worse time-in-range than I could achieve on my own care. (It was like two people with their hands on the steering wheel!) After a few weeks, I learned to co-pilot with Loop. I expect many early adopters of automated insulin delivery systems will have a similar learning curve.

Q: If you could wave a magic wand, what is the #1 thing you would change about your DIY system?

The biggest weak point of Loop is it only works with out-of-warranty Medtronic pumps, and these pumps require a RileyLink communication bridge to talk to a phone – that’s another device to charge and to carry around. The system would actually be safer and more effective if pumps were designed with Bluetooth to seamlessly communicate directly with the Loop app. For the current DIY version of Loop, getting and safely using an old Medtronic pump is the biggest problem. (This is also a major reason Kelly is not using Loop, as you’ll see in her edition of this column next month.)

Fortunately, pumps designed with Bluetooth to seamlessly communicate directly with the Loop app are coming: Insulet’s Omnipod is the first pump partner for Tidepool Loop, and diaTribe fully expects other companies to follow. Loop is too good not to integrate with! Pumps compatible with Loop will be a terrific option, alongside companies developing their own systems.

Q: What will it take for you to move from your DIY system to a commercial closed loop system?

The Medtronic pump I’m using is probably ten years old, which is way past its intended four-year life – it will malfunction at some point, probably at an inconvenient time. When it breaks, I’ll consider all the options available, which will hopefully include Tidepool Loop.

As mentioned, Medtronic already has a hybrid closed loop available – the MiniMed 670G. Tandem’s Control-IQ hybrid closed loop should be the next system on the US market, expected to launch next summer (2019). Notably, Control-IQ will add automatic boluses for high blood sugars, in addition to basal automation.

Between 2-4 more systems are likely to launch by the end of 2020, including Beta Bionics iLet (insulin-only), Bigfoot Loop, Lilly, and Medtronic’s next-gen closed loop with auto boluses. There will be many choices on the market in the next 2-3 years!

Q: What is the biggest public misunderstanding about DIY systems?

Some worry that “DIY” systems are unsafe. The reality is that dosing insulin manually is even less safe than a properly constructed automated insulin delivery system – any level of automation is likely to help most people. Loop has been around long enough to take seriously. However, it’s true that Loop doesn’t have the same level of FDA oversight and the clinical trial data that we’d see with a commercial product.

I have zero software coding experience and approached Loop cautiously. A few things convinced me to try it:

-

Loop is much safer than going to bed with the same basal rate every single night and sleeping through my low or high CGM readings.

-

Loop only adjusts basal insulin (no automatic boluses), and I can set a maximum basal rate (the system cannot increase insulin delivery infinitely).

-

I see very good accuracy with Dexcom CGM, aligning closely to fingersticks.

-

For the first week, I used the Loop app with “closed loop” turned off, meaning I was on my own manual dosing and could watch Loop’s “recommended” dosing strategy. This helped me understand how it worked before turning “closed loop” on.

-

Some parents are using Loop on their own kids. That to me is the ultimate test of confidence in a system.

Q: What is the #1 piece of advice you would you give to someone considering a DIY or commercial closed-loop system?

Although closed loop is amazing, try to have reasonable expectations! Closed-loop systems are not a cure; they are another tool in the box, and the effectiveness of the tool depends on proper training and proper application.

For the vast majority of people, closed loop is going to dramatically improve nights – real-time automation based on CGM readings is always going to do better than I can manually while I’m asleep. Starting most days at a glucose of 90-120 mg/dl is absolutely phenomenal.

During the day, there is a learning curve for meals, for exercise, for treating lows, and for troubleshooting – and it may require changes in habits.

With current technology, no closed-loop system works 100% of the time, and systems do require some manual input (e.g., “I’m going to eat”). On a hybrid closed loop, the insulin steering wheel is both automated and manual, which makes us co-pilots – not passive passengers.

For those looking forward to closed-loop systems, don’t expect perfect blood sugars all the time, the ability to eat anything, or “not to ever think about diabetes.” But that’s okay – all we’re looking for is improvement!

Click here to go back to the table of contents.

Concluding Thoughts

Overall, my experience with Loop has been really surprising, since it has improved my life with diabetes far more than I expected. I’m a big believer in the potential for automated insulin delivery to level the playing field in diabetes care – offering improved time-in-range (especially overnight) and less burden to a wider spectrum of people with diabetes.

But we must be vigilant: will these products be reasonably priced, show high value, and be widely covered by insurance companies? Hopefully by sharing our stories, we can document the benefits of these technologies.

Though only a few thousand people are probably going to use this DIY version of Loop, sharing real-life experiences are extremely important – the community can help inform development, design, and evidence for commercially available closed-loop systems.

***

We’ll share more Loop user stories in issues to come, with Kelly’s experiences coming up next! If you’d like to contribute to our series, view the questions and instructions here.