Hard to Lose Weight, Harder to Keep it Off – A Remarkable New Study Explains Why

by mark yarchoan

by mark yarchoan

For years, studies have confirmed what is obvious to anybody who has tried to lose weight: weight loss is challenging, and keeping lost weight off is even harder. In 2005, a landmark study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association comparing a number of popular diets – Atkins (carbohydrate restriction), Zone (macronutrient balance), Weight Watchers (calorie restriction), and Ornish (fat restriction) – found that all of the most popular diets are similarly ineffective. At the end of one year, people who had attempted to diet using any of these strategies lost an average of only about five pounds. Other studies have found that more than 90% of people who lose a lot of weight eventually gain the weight back.

These studies should not be considered a reason or excuse to avoid dieting. Even small amounts of weight loss and changes in lifestyle can have truly dramatic effects on health, including improved blood pressure and glucose control for people with diabetes. However, it is important to have realistic expectations about weight loss, because weight loss involves fighting a set of embedded forces in the body that are designed to prevent weight change. Although the conscious brain may be saying, “it’s time to lose weight”, a complex interplay of weight-related hormones may be saying something different.

The average American eats over 70 million calories in a lifetime, plus or minus a couple of million calories. Yet incredibly, for most people, body weight is kept within a relatively narrow range. Over the course of a decade, food intake and energy output is typically matched within 0.17%. This means that for almost everyone of any kind of build or weight, calories in and calories burnt are kept virtually equal. Working behind the scenes is a complex interplay of hormones and neuronal circuits that control hunger and metabolism so that both sides of this energy equation remain equal. This Learning Curve attempts to explain what these hormones are, how they work, and why their existence makes weight loss so challenging.

leptin: a long-term regulator of fat

Originally discovered in 1994 by Dr. Jeffrey M. Friedman at the Rockefeller University, leptin is thought to be one of the most important regulators of weight. Children born with a rare genetic deficiency in leptin become morbidly obese at a young age, and their weight can be mostly normalized when leptin is administered to them. Leptin is secreted from fat cells and acts somewhat like a thermostat for weight. When a person gains weight, more leptin is produced, causing a decrease in appetite and an increase in energy metabolism. When weight is lost, the opposite happens.

It’s easy to understand why leptin makes successful dieting so difficult. When a person starts dieting, leptin levels fall dramatically even with modest weight loss. The fall in leptin is sensed by the brain, and the dieter begins to experience increased appetite. In addition, a fall in leptin levels makes high-calorie food taste better, and eating begins to feel more rewarding. As a result of low leptin levels, dieters may actually crave high calorie foods like potato chips. In addition to promoting increased calorie intake, the fall in leptin also decreases metabolism by making the body more efficient. Fewer calories are burned in muscle and other tissues at rest and while exercising. These converging effects of a fall in leptin – increased appetite and decreased energy metabolism – may explain why so many dieters regain weight that they worked so hard to lose.

a hormone network dedicated to maintaining weight

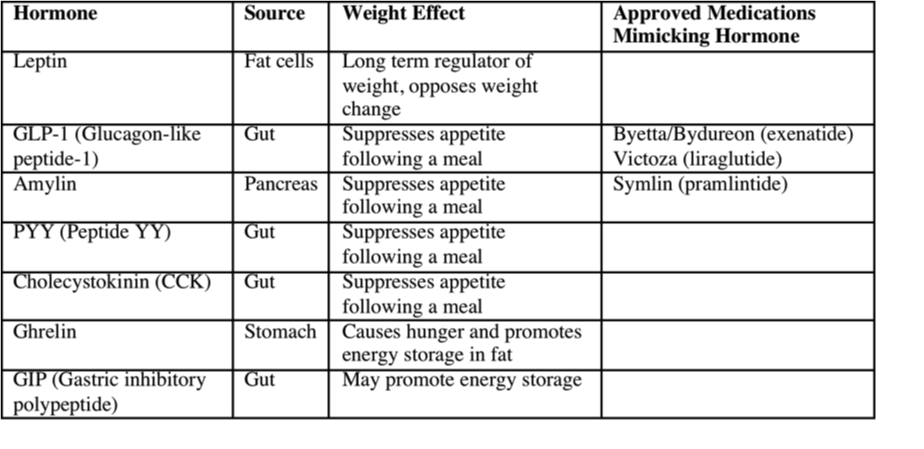

A number of other hormones effect whether a person feels hungry or full at any particular time of the day. Cholecystokinin (CCK), peptide YY (PYY), amylin, and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) are hormones that are secreted by the gastrointestinal tract and pancreas in response to a meal and act on the brain to suppress appetite. A different hormone, ghrelin, is secreted from the stomach when it is empty, and causes hunger. Many of these hormones have been shown to interact with leptin and with each other, and so for example high levels of leptin plus amylin may cause more satiety than high levels of either hormone alone.

Table: Obesity-related hormones that effect appetite and metabolism and are thought to work together to resist body weight change.

Table: Obesity-related hormones that effect appetite and metabolism and are thought to work together to resist body weight change.

What happens to all of these weight-related hormones when a person loses weight? That question was recently answered in an important study conducted by a group of Australian researchers lead by Dr. Priya Sumithran that was published in the October 27 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine. The researchers recruited overweight people and put them on a strict diet (500 to 550 calories a day) that caused them to lose at least 10% of their body weight and kept them on a diet that would maintain the weight loss for one year. At the end of the year, the participants had significant changes in their obesity-related hormones. For example, leptin levels had fallen by about two-thirds when the subjects initially lost weight, and were still one-third lower at the end of the one-year study period even though participants had regained much of the lost weight. Other obesity-related hormones including those listed in the chart above were also changed. Going along with changes in hormone levels, participants were also found to have increased appetite and decreased metabolism. These results suggest that multiple hormones change in response to weight loss and they continue to encourage weight regain for at least a year after a person has lost weight.

Taken together, all of this scientific evidence creates a compelling story of why weight loss is so challenging for most people. When weight is lost, multiple hormones controlling hunger and metabolism work together to cause weight regain. The greater the weight loss, the greater the hunger and the lower the metabolism, and unfortunately for most dieters the urge to eat eventually trumps a conscious desire to be thin.