My Appendix Ruptured: Scary Lessons Learned About Diabetes in the Hospital

By Adam Brown

By Adam Brown

By Adam Brown

How I managed my blood sugars after emergency surgery, IV dextrose madness, why CGM is desperately needed in the hospital, the ludicrous cost of fingersticks, and more

We've known for a long time that diabetes care in hospitals is often bad, but until you experience it personally – and you have to go to the ER and have an emergency surgery and stay there for five days – you don’t truly understand how unprepared hospitals are.

My experience last month left me deeply concerned about anyone with diabetes who has to go into any hospital. Because I'm proactive and knowledgeable, I was able to take control of my own care and navigate my way through, but it was not easy. Even though I was admitted to one of our nation’s finest hospitals, University of California at San Francisco, at times I had to override doctors’ orders to ensure my own safety.

Most experts told me I was “lucky” to get this level of care, since my experience was “better than most.” That is a testament to the very capable UCSF team, but also a warning: we should all be concerned about hospital diabetes care. The tools must get better to manage blood sugars in the hospital; people with diabetes and care providers deserve much better.

Here's exactly what happened to me and some surprising lessons that followed.

What Happened

On Thursday, August 30, I woke up in the middle of the night vomiting uncontrollably. I assumed I had eaten something questionable, but I couldn’t pinpoint exactly what.

The next morning, I was too sick to do anything. In over 2,000 days of full-time work at diaTribe and Close Concerns, I have never taken a sick day, but there was no question on this morning: my stomach was in so much pain that I could barely walk. I had no interest in even drinking tea, which would be a shocking revelation to people who know me. My blood sugars were higher than usual, even while my do-it-yourself automated insulin delivery system (Loop) was delivering about 30%-50% more insulin to bring me back to target. I was not eating anything.

On Saturday, I decided to go to urgent care two blocks away, assuming I had some really bad food poisoning. The kind physician assistant agreed and gave me a powerful anti-nausea medication, Zofran. He handed me a glass of watered-down apple juice, which I sipped slowly and did not immediately throw up. Success!

Although the vomiting stopped, the diarrhea started. As the profound stomach pain continued, it was clear I was not getting better. By Sunday morning, with the diarrhea now appearing black, continued Internet research, and my girlfriend, Priscilla, just getting home from an East Coast trip, we agreed: it was time to go to the emergency room.

The ER nurse took my vitals, and I measured a fever for the first time since I got sick three days earlier. I was ushered to a room and hooked up to IV fluids, as I hadn’t eaten in three days. The attending doctor pressed on my abdomen and decided a CT scan was warranted – “We’re thorough here in the ER.”

Results from the first CT scan of my life came about an hour later, delivered by a new energetic doctor: “You have appendicitis, and we’re going to put you into surgery tonight. We do at least one of these a day, and it’s a very straightforward laparoscopic (minimally invasive) procedure that takes about 30-45 minutes. Most people are in and out of the hospital in 24 hours, unless their appendix is ruptured."

The next hour moved fast. I signed a waiver stating that I would continue to manage my own blood sugar in the hospital, using my own insulin pump and CGM.

I was wheeled up to the bright, chilly operating room floor, and just like in the movies, a whole team bustled around, prepping for surgery and hooking me up to things. I confirmed my pump should keep running the usual basal rate. (I couldn’t run DIY closed loop, as my phone was not with me in the OR.)

The oxygen mask went on ("breathe deeply”), the anesthesia did its job, and I woke up from surgery about two hours later.

It turns out my appendix had indeed ruptured (burst), a more serious issue than the usual inflamed appendix – requiring a longer surgery to remove the appendix and to clean my abdominal cavity. Worst of all, a ruptured appendix brings a much higher risk of post-surgical infection.

I spent the following 4.5 days in the hospital, including four days of IV antibiotics. I didn’t go to the bathroom on my own for two days. I didn’t eat for seven days and lost 10 lbs (6% of my bodyweight). This was easily the sickest and most incapacitated I’ve ever been in my life.

Three weeks later as I write this, I’m nearly 100% recovered and am back to normal activity, eating, and writing. Here are some of the lessons I’ve learned and reflected on since leaving the hospital.

Managing Blood Sugars in the Hospital and Why They Matter

I’ve attended hundreds of diabetes conferences over the past eight years and seen many talks about the importance of blood sugars in the hospital. If I had to summarize the research quickly, it would be:

-

High blood sugars matter in the hospital. In most studies, higher blood sugars are strongly associated with higher infection rates, longer length of stay, and even a higher risk of death. For some of the research, click here.

-

Blood sugars can run very high in the hospital for all sorts of reasons – e.g., the stress of illness can cause highs, IV fluids often contain dextrose that raises blood sugar (more on that below), certain medications can cause hyperglycemia (glucocorticoids), activity levels are low, most hospital food is high in carbs, etc. It’s a 42 factors nightmare!

-

Hospitals are understandably terrified of hypoglycemia, which is also linked to very bad outcomes, including a higher risk of death. Medicare considers severe hypoglycemia as a “never event,” meaning a hospital will not get paid if it occurs.

-

Fingersticks are done very infrequently, and CGM is never used in the hospital.

Bottom line: Keeping blood sugars in a tight range (70-140 mg/dl) in the hospital is very difficult, walking the tightrope between highs and lows (both bad) in tough conditions with very few data points from fingersticks.

Bottom line: Keeping blood sugars in a tight range (70-140 mg/dl) in the hospital is very difficult, walking the tightrope between highs and lows (both bad) in tough conditions with very few data points from fingersticks.

Knowing this, I told the UCSF staff I would manage my own blood sugars using my own pump and CGM. Once I was out of surgery – where my pump just delivered a flat basal rate – I resumed running my DIY Closed Loop, which adjusts basal insulin automatically every five minutes based on the Dexcom G6 CGM.

UCSF thankfully let me sign a waiver saying I would manage my own diabetes – some hospitals don’t even allow people to do this or don’t mention it as an option. I only had to do two things: (i) allow nurses to take fingersticks with the hospital meter as part of my vitals; and (ii) inform nurses of any insulin doses I was taking. I didn’t eat anything for most of my hospital stay, meaning the automated basal adjustment could keep my blood sugar in range with no input from me.

I was at one of the leading hospitals in the United States, but it was clear from the first 12 hours that the team would have struggled to manage my blood sugars.

The best example of this came just a few hours after surgery, when the nurse measured a blood sugar of 221 mg/dl on the highly accurate Accu-Chek Inform II hospital meter. My own Dexcom G6 CGM said 223 mg/dl.

The best example of this came just a few hours after surgery, when the nurse measured a blood sugar of 221 mg/dl on the highly accurate Accu-Chek Inform II hospital meter. My own Dexcom G6 CGM said 223 mg/dl.

Though it was 2:11 am, I was pretty awake and knew 221 mg/dl was an issue – a big risk with a ruptured appendix is infection, and hyperglycemia at this level is a problem.

In one study, people with diabetes measuring glucose levels over 220 mg/dl on the first post-surgery day had an infection rate 2.7 times higher than those with glucose levels less than 220 mg/dl. (Yep, that was me.) In another study, post-surgery blood sugars over 180 mg/dl doubled the length of hospital stay (12 days) vs. those with blood sugars under 140 mg/dl (6 days).

I firmly remember the nurse was not at all worried by 221 mg/dl. I told her I was going to take four units of bolus insulin to correct it, which was actually a conservative dose in the context of post-surgery stress. She said the doctor recommended “two units.” I told her I would need at least “four,” and she countered that the doctor would need to confirm it before I took the dose.

About 45 minutes later, she came back with a surprise: “The doctor actually recommends you take ten units.” It was 3 am by this point, but I was alert and responded firmly: “No, that’s ridiculous. Ten units might put me into severe hypoglycemia. I’m taking four units. Let the doctor know.”

This was an egregious example, but a real reminder for me.

Lesson #1: If you are alert and capable, consider managing your own blood sugars in the hospital.

You know your diabetes better than the hospital staff. (Loved ones can also help, especially in the case of pediatrics.) If you wear CGM, absolutely continue to wear it in the hospital, even if the team is managing your diabetes for you.

You know your diabetes better than the hospital staff. (Loved ones can also help, especially in the case of pediatrics.) If you wear CGM, absolutely continue to wear it in the hospital, even if the team is managing your diabetes for you.

In many hospitals – including UCSF – the endocrinology team should come by to check on you, especially if you are using your own devices. The team did visit me a few times, but was not involved in any decisions about my insulin dosing or glucose management.

Hyperglycemia From IV Dextrose

In the 24 hours after surgery, I resumed wearing Loop, meaning my pump’s basal rate was automatically adjusted every five minutes to bring my blood sugar to target. Here’s my 24-hour glucose trace from right after surgery (left side) to 24 hours later:

And the statistics to accompany it:

I needed 64 units of insulin on this day, which is double the amount I normally take and included 21 units of manually delivered bolus insulin that I took to try to get my blood sugar back to target. I didn’t eat or drink a single calorie, and yet, I came nowhere close to blood sugars that would likely prompt the best recovery and lowest risk of infection.

And then I connected the dots: the IV fluids I was receiving contained dextrose (glucose). I asked the nurse if they could switch me to an IV that did not contain dextrose, which she happily did starting close to midnight (right side) in the graph above.

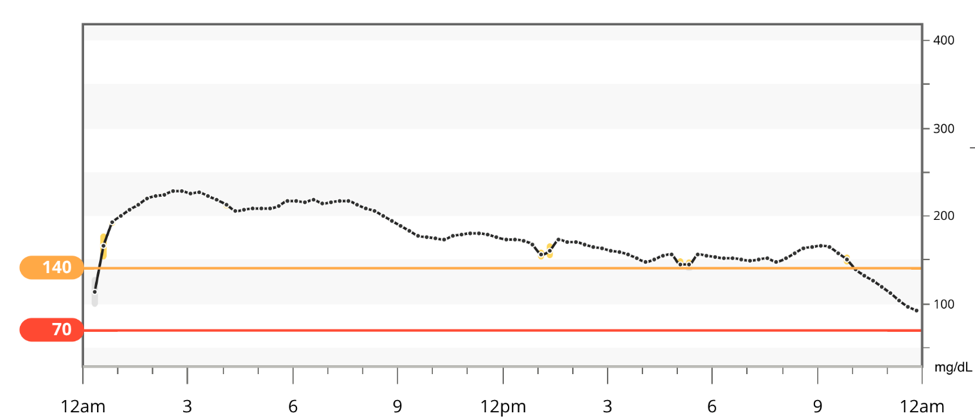

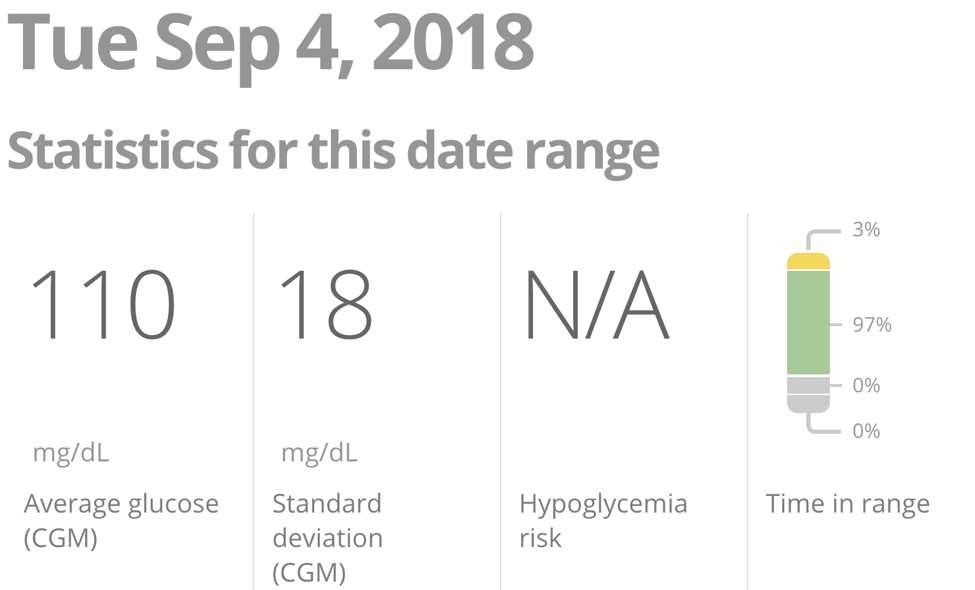

Here’s the CGM data from the rest of that night and across the next day:

And the statistics to accompany it:

It was a stunning improvement: my glucose improved from an average of 176 mg/dl to 110 mg/dl, with time-in-range (70-140 mg/dl) going from 10% to 97%. That improvement was also delivered with half as much insulin – 30 units! (I wasn’t eating on either day.) It’s possible that a reduction in post-surgery stress contributed to this day #2 improvement, but the timeline shows switching to the non-dextrose IV made a powerful and immediate impact.

Lesson #2: If you are managing your own blood sugars, beware of IV fluids with dextrose/glucose – they will raise blood sugar and require much more insulin.

Getting off IV dextrose in the hospital is not always an option, but there is no harm in asking – including if a lower concentration dextrose solution is an option. This was not even mentioned! Dr. Irl Hirsch told me that some insulin users routinely run blood sugars in the 300 mg/dl range in the hospital, as insulin doses are not increased enough to compensate for the dextrose.

This also relates to a broader point that applies both inside and outside the hospital: always ask what medications you are getting, why you are getting them, what function they perform, how they might affect blood sugars, and (if results are not ideal) what your other options are.

This also relates to a broader point that applies both inside and outside the hospital: always ask what medications you are getting, why you are getting them, what function they perform, how they might affect blood sugars, and (if results are not ideal) what your other options are.

Geeky aside: Several experts told me that IV dextrose use is “complex” in people with diabetes. Dr. Daniel DeSalvo mentioned that it is probably overused in people with diabetes, but often times it may be necessary – e.g., very small or very sick patients that are not eating. However, it is not clear, said Dr. Irl Hirsch, how much IV dextrose and insulin are enough in someone not eating by mouth. What worked in my case – no dextrose, only basal insulin, careful CGM observation – won’t work in all cases. Dr. Jake Kushner reminded me that the risk of DKA can also rise if both IV dextrose AND insulin are stopped, which can happen in the hospital (e.g., IV falls out). In my case, basal insulin was flowing fine through my pump and my blood sugars had normalized (see above), so DKA seemed like a very low risk.

The Desperate Need for CGM In the Hospital

In my five days spent at UCSF, the team took a total of 22 fingersticks. (I know the exact number because they all appear in MyChart, an electronic medical record portal I can log into from home to view hospital and lab test results.)

By contrast, I received 1,440 glucose data points from my Dexcom CGM across five days – 288 per day. The G6 CGM had awesome hospital performance, rarely more than 10-15 mg/dl off the hospital meter. Notably, this was on a backdrop of high doses of acetaminophen (Tylenol). As we said in our test drive of G6, the accuracy without fingersticks really delivers.

Not a single nurse at one of the finest hospitals in the country had heard of CGM – all were completely blown away that I could receive a real-time glucose reading on my phone and alarms for highs and lows. “Why do we not have this?!!!” was a common, slightly enraged sentiment.

This did not surprise me, but it is also maddening. I’ve been wearing CGM for nearly ten years, and it is still used by a minority of people with type 1 diabetes and very few people with type 2 diabetes outside of the hospital. Given what I experienced, CGM feels wildly far from any meaningful use in the hospital – at least ten years away and probably longer. I desperately hope I’m wrong, as this lag time is a travesty; CGM would unquestionably save lives in the hospital, prevent wasted nursing time taking fingersticks, and help get people out of the hospital faster.

This did not surprise me, but it is also maddening. I’ve been wearing CGM for nearly ten years, and it is still used by a minority of people with type 1 diabetes and very few people with type 2 diabetes outside of the hospital. Given what I experienced, CGM feels wildly far from any meaningful use in the hospital – at least ten years away and probably longer. I desperately hope I’m wrong, as this lag time is a travesty; CGM would unquestionably save lives in the hospital, prevent wasted nursing time taking fingersticks, and help get people out of the hospital faster.

The cost of fingersticks in the hospital is also forgotten. My all-in trip to UCSF – including the ER, surgery, and four-night stay – generated a jaw-dropping total “bill” of $129,459. I use quotes because this is sort of a phantom number; my Aetna claims show insurance paid a discounted rate of $44,693, or one-third of that full price. (I paid $2,950 out of pocket.) Out of curiosity, I dug into the bill and learned that each fingerstick was originally billed at a ridiculous $226 each! If Aetna similarly paid one-third of the originally billed cost, the 22 fingersticks over five days cost the system an estimated total of $1,690. At ~$77 per strip, that is ludicrous, even if it includes some hospital overhead bundled in. That same $1,690 would cover six months of CGM outside of the hospital for someone paying cash.

To me, this captures the complete dysfunction of our health care system in one detail.

.png)

Lesson #3: CGM will change the game in the hospital, helping nurses and patients keep blood sugars in range, catch hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia quickly, and probably lower costs.

CGM should be a slam dunk for hospital efficiency too, since it can help save nursing time. Unfortunately, many experts I’ve talked to are not that optimistic about the speed at which CGM is moving into the hospital – the studies are hard and expensive to do, the FDA has high standards for hospital monitoring, and hospitals adopt new things slowly since the training burden is so high, especially for floor nurses. I think the best we can do for now is: (i) wear your CGM in the hospital so nurses see the value; and (ii) advocate for many more studies of CGM in the hospital! Continuous cardiac monitoring is already common; why not diabetes too?

Geeky aside #1: There is an ongoing debate about optimal glucose range in hospital/critical care settings, a moving target that may continue to evolve as more studies are done with CGM. Conservative targets of 140-180 mg/dl are commonly used in many hospitals; however, if the infamous NICE SUGAR study (2009) was repeated with CGM, severe hypoglycemia probably could have been avoided, potentially driving a much different outcome.

Geeky aside #2: Even for experienced endocrinologists, achieving tight blood sugars in the hospital can be very challenging, especially for very sick patients on multiple medications. Indeed, Dr. Daniel DeSalvo noted that many of the 42 Factors that affect blood sugar are truly amplified in the hospital setting. This is why I’m such a huge fan of CGM to help unpack the complexity and warn of danger quickly. Ultimately, automated insulin delivery with CGM and continuous insulin infusion should drive the best outcomes, and Dr. Roman Hovorka’s team has done some compelling early studies on this front – see here and here.

Hospitals Do Not Prioritize Sleep

The book Why We Sleep by Dr. Matthew Walker (column coming soon) makes a compelling case for the restorative, health-transforming power of sleep, as well as the health-destroying effects of too little rest. Sleeping too little (i.e., less than 7 hours) impairs many of the body’s systems that are critical for recovery, including immune function, blood sugars, and how the brain perceives pain.

As I recovered from surgery, I was struck by how poorly I slept – probably closer to 5-6 hours per night – and how hard it was to fall asleep and remain asleep in the hospital. This is apparently common after surgery, but the hospital’s policies and design made things so much worse. Sleep was not a priority.

Vital signs were measured every four hours in my first few days after surgery, which fragmented my sleep. On top of that, medication doses were often staggered in between vitals, meaning some nights I was awakened every couple of hours. This is a disaster for restfulness!

Vital signs were measured every four hours in my first few days after surgery, which fragmented my sleep. On top of that, medication doses were often staggered in between vitals, meaning some nights I was awakened every couple of hours. This is a disaster for restfulness!

I was so frustrated by the third day that I urged the nursing staff to stagger my vital signs and medications in a smarter way, giving me more uninterrupted sleep. It definitely helped.

I also used the rain sounds on the app Calm to fall asleep each night with earbuds in – more conducive to sleep than the constant hallway whirring of the hospital. Thankfully, it was possible to make my room very dark, though some doctors would roam in, turn lights on, and then exit the room brusquely without turning them off.

By day four in the hospital, I was desperate just to go home so I could sleep in my own bed – I knew I would recover faster with uninterrupted, comfortable sleep.

Lesson #4: Restorative sleep should be thought of as recovery medicine in the hospital.

Hospitals could improve sleep with better staggering of vitals and medications (less interruption), along with many of the other tips I discuss in Bright Spots & Landmines. Even little improvements are meaningful: Why We Sleep mentions powerful research in the neonatal intensive care unit, studying the impact of lighting. Babies with improved lighting conditions that prioritized sleep – dim during the day, blackout at night – left the hospital five weeks earlier!

Seeking Care – Where and When?

In retrospect, my decisions on where and how quickly to seek care are also fascinating. I took a stepwise approach: internet research (free, immediate), call insurance company nursing line for advice (free, immediate), go to urgent care ($25 copay, 1 hour), and go to emergency room ($300 copay, several hours). I clearly should have gone immediately to the ER and might have even caught my appendix when it was simply inflamed – not ruptured.

But in the moment, I thought it was silly to pay a $300 ER copay and to spend many hours to likely be told I had food poisoning. I did not measure a fever at home, and my blood sugars were high but not crazy. The staggered approach made sense at the time, since I was convinced I had food poisoning. I am truly glad I went to the ER when I did; a ruptured appendix can be deadly, and I shudder to think at what would have happened with another day or two.

Lesson #5: Make sure to escalate quickly if things are not getting better.

Urgent care is great for a lot of things, but more serious issues – especially for those of us with diabetes – may deserve a look at the ER. “Waiting another day” is an easy trap to fall into; with health problems, catching them earlier is always better. Sharing symptoms with a loved one can also help you be objective – in my case, Priscilla provided the impetus to actually go to the ER.

Urgent care is great for a lot of things, but more serious issues – especially for those of us with diabetes – may deserve a look at the ER. “Waiting another day” is an easy trap to fall into; with health problems, catching them earlier is always better. Sharing symptoms with a loved one can also help you be objective – in my case, Priscilla provided the impetus to actually go to the ER.

A Mental Reset: Profound Gratitude

After this hospital scare, I’ve had a profound mental reset, a sort of post-surgery glow at how precious good health is and how much it should be treasured. It’s truly easy to forget this on a daily basis!

This lesson actually helped me cope with the hospital stay too, since I viewed the entire ruptured appendix saga as a reminder to be profoundly thankful for good health, rather than some horrible thing that never should have happened to me.

Lesson #6: Gratitude is a powerful coping strategy, especially when unfortunate events inevitably happen.

We cannot control everything that happens to us, but we can always control our response to it.

***

Please send questions and feedback here! A tremendous thanks to the following brilliant minds who reviewed this article and provided comments: Dr. Rich Bergenstal, Dr. Daniel DeSalvo, Dr. Claudia Graham, Dr. Irl Hirsch, Jim Hirsch, Dr. Jake Kushner, Dr. Robert Vigersky, and Ms. Gloria Yee.

.jpg) Would you like to read my top food, mindset, exercise, and sleep tips? My book, Bright Spots & Landmines: The Diabetes Guide I Wish Someone Had Handed Me, has been sold/downloaded over 80,000 times! It is available as a…

Would you like to read my top food, mindset, exercise, and sleep tips? My book, Bright Spots & Landmines: The Diabetes Guide I Wish Someone Had Handed Me, has been sold/downloaded over 80,000 times! It is available as a…

-

Free PDF download or buy it in paperback ($6), or Kindle ($1.99)

-

Free audiobook on diaTribe or YouTube, or buy it at Audible, Amazon, iTunes

-

mmol/L version: free PDF and in paperback at Amazon UK and Amazon Canada