Are all carbohydrates created equal?

By Adam Brown

by Adam Brown

by Adam Brown

twitter summary: All carbs are NOT created equal - 30 g of beans is way different from 30 g of glucose tabs; choose lower glycemic index foods for better BGs

A diagnosis of diabetes – type 1 or type 2 – hits everyone very differently. However, one common memory for most of us is learning about food and carbohydrate counts. To this day, I still haven’t forgotten that one cup of milk contains 12 grams of carbs, one cup of rice contains 45 grams of carbs, and a steak doesn’t have any carbs. We also pretty quickly learn the physiology basics: a carbohydrate raises blood sugar, and the more carbs you eat, the larger the blood sugar spike (all else being equal). Those of us on insulin estimate the appropriate amount to cover the carbohydrates and bring our blood glucose back down – e.g., if I eat 30 grams of carbs, I should take three units of insulin (for someone with a 1:10 insulin-to-carb ratio). If I eat 60 grams of carbs, I need six units of insulin. Pretty simple.

However, that approach embeds what seems like an illogical assumption - namely, that all foods containing carbohydrates are created equal. In other words, if I eat an equal number of carbs of two very different foods – half a cup of black beans (30 grams of carbs) and 7.5 glucose tablets (30 grams of carbs) – I should still take the same three units of insulin. Is that really true?

In a few simple experiments using my CGM, I found that this was not at all the case – at least for me. The same 30 grams of carbs of black beans and glucose tablets yielded strikingly different results in blood glucose. I’ve done two head-to-head trials comparing both foods – one without insulin (a baseline) and one with insulin. Below, you will find the results of my trials, along with a short review of the research and tips for reducing glucose spikes. A caveat: this article reflects my personal experience and the results may not translate to all patients in all cases. I’ve lived with diabetes for 12 years, but am not a healthcare professional. It’s best to consult your healthcare provider before making any changes to your diet or medication regimen.

Case Study 1: Black Beans vs. Glucose Tablets – No Insulin

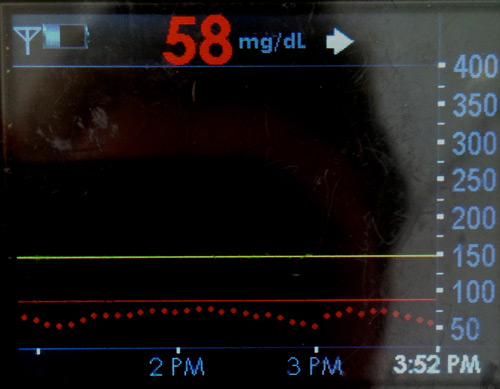

As you can see from the table below, in the absence of insulin, glucose tablets caused more than double the rise in my blood glucose (+97 mg/dl) vs. black beans (+40 mg/dl), even though the number of carbohydrates (30 grams) and my starting blood glucose (69 mg/dl) were the exact same.

|

Case Study 1: No Insulin |

||

|

|

Blood Glucose Trend |

Blood Glucose Change |

|

Black Beans – 30 grams of carbs (½ cup) |

69 mg/dl → 109 mg/dl |

+40 mg/dl |

|

Glucose Tablets – 30 grams of carbs (7.5 tablets) |

69 mg/dl → 166 mg/dl |

+97 mg/dl |

Note: These tests (and those below) were certainly not done in a lab setting, but I did keep as many things constant as possible: I did not exercise in the post-meal observation period, I checked blood glucose at the same consistent time, I did not have insulin on board going into the test, I had a steady-state blood glucose going into the test, and I did the tests within 24 hours of each other.

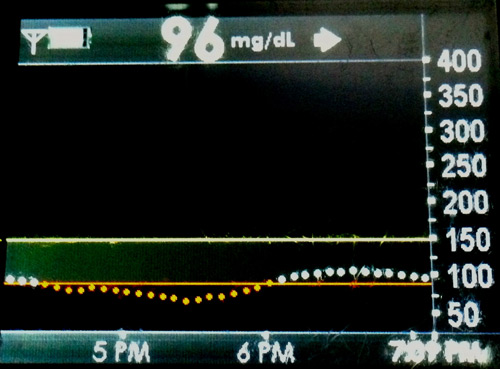

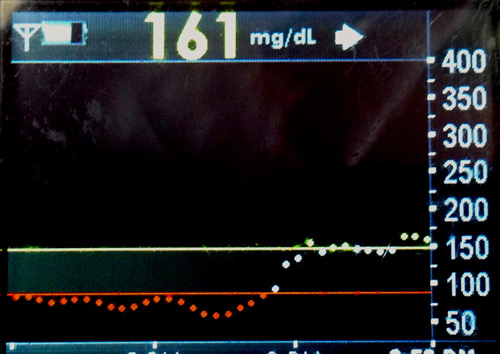

Black Beans Glucose Tablets

Adding Insulin to the Mix

The above scenario is instructive and a good baseline, but what would happen if the appropriate amount of insulin was taken to cover the meal? You can see the results of those experiments below. In short, the overall three-hour glucose change was the basically the same in both experiments (+3 mg/dl with black beans vs. +10 mg/dl with glucose tablets, but the difference came in peak blood glucose – 80 mg/dl with black beans vs. 165 mg/dl with glucose tablets. The CGM traces put it most clearly: after eating black beans, I had a flat line trace at 70-80 mg/dl, while after eating glucose tablets, I saw a dramatic rise and subsequent fall.

|

Case Study 2: Adding Three Units of Insulin |

|||

|

|

Blood Glucose Trend |

Blood Glucose Change |

Peak Blood Glucose (via CGM) |

|

Black Beans – 30 grams of carbs (½ cup) |

70 mg/dl → 73 mg/dl |

+ 3 mg/dl |

80 mg/dl |

|

Glucose Tablets - 30 grams of carbs (7.5 tablets) |

114 mg/dl → 124 mg/dl |

+10 mg/dl |

165 mg/dl |

Note: See note above for the basics of what I held constant in these experiments. In these cases with insulin, I took three units right before eating and measured blood glucose exactly three hours after the meal. In the above case without insulin, a 90-minute post-meal test was sufficient, as my glucose had reached a steady-state peak; when insulin was added, a full three hours was needed to observe the full glucose-lowering effect.

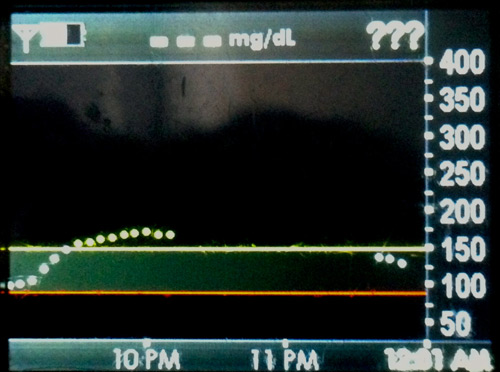

Black Beans Glucose Tablets

Note: The gap in data and "???" symbol in the picture to the right reflects a period of time where the CGM was not reading my glucose levels. This happens rarely with the Dexcom G4 Platinum. Still, looking at the beginning and end of the three-hour graph illustrates what happened after eating 30 g of glucose tablets and taking insulin - a quick rise in glucose with a subsequent fall.

A Primer on Glycemic Index

An important factor at play here is something called “glycemic index.” A glycemic index ranks carbohydrates on a scale from 0 to 100 according to how much they raise blood sugar levels. Foods are assessed in a laboratory setting and a glycemic index value is assigned to them (specific details here). Pure glucose serves as a reference point and is given a glycemic index of 100.

A high glycemic index (>55) means a food spikes blood glucose more rapidly than a food with a low glycemic index (<55). In my examples above, glucose tablets (made of dextrose) have a very high glycemic index of 96. Black beans, by contrast, have a very low glycemic index of 30. For further context, peanuts have a super low glycemic index of 13, brown rice has a medium score of 48, and white potatoes have a score of 96. To search the glycemic index of foods you typically eat, click here (since these require lab experiments, the database is not 100% comprehensive).

What does the research say about glycemic index and glucose control?

The above examples were just two foods and a handful of personal experiments – what does the scientific literature have to say about glycemic index and whether all carbs are created equal? The research in this area is unfortunately quite mixed – some studies show a benefit on diabetes control when choosing lower glycemic index foods, while other studies show no effect. I have selected a handful of studies below, though this is just a snapshot of the broad and mixed research in this area.

-

In a comprehensive 2009 Cochrane review of 11 studies in 402 people with diabetes, researchers concluded “a low-GI [glycemic index] diet can improve glycemic control in diabetes without compromising hypoglycemic events.” Indeed, A1c was 0.5% better in those on low glycemic diets, and in two trials, hypoglycemia was less frequent.

-

A 2008 review paper in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition highlights studies in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes that show significantly lower blood glucose levels with lower glycemic index diets/foods. The review draws the same conclusion I did: “…it is known that not all carbohydrate-rich foods are equally hyperglycemic…even when consumed in portion sizes containing identical amounts of carbohydrate.”

-

The newly published American Diabetes Association Nutrition Therapy Recommendations highlighted mixed results on this topic. The paper notes, “Some studies did not show improvement with a lower-glycemic index eating pattern; however, several other studies using low-glycemic index eating patterns have demonstrated A1c decreases of -0.2% to -0.5%. However, fiber intake was not consistently controlled, thereby making interpretation of the findings difficult.” The authors emphasize that the literature on this topic is complex, definitions vary across studies, and there are many confounding variables.

What are the implications for people with diabetes?

Overall, the message from my own experiments and some of the research is that all carbohydrates are NOT created equal! Foods with a high glycemic index spike blood glucose much more quickly and could potentially lead to worse glycemic control relative to lower glycemic index foods. My tests above showed a big difference in terms of glycemic profiles – lower glycemic index (in this case black beans) was the way for me to to achieve better control. In my opinion, the nice thing about eating lower glycemic index foods is they really can provide a cushion (or a head start!) against the limitations of slow insulin absorption.

That said, I want to echo the ADA’s latest nutritional recommendations linked above: “…there is not a “one-size-fits-all” eating pattern for individuals with diabetes.” Put differently, what works for me may not work for everyone! I would love to hear what has been successful for you – feel free to email me at adam.brown@closeconcerns.com.

Five Ways to Reduce After-Meal Glucose Spikes

1. Go for a lower glycemic index food – If you take away one lesson from this article, I hope that it’s in the value of choosing foods with a lower glycemic index. For starters, you can find lists here and here, though you can also search for foods here. In general, I would recommend opting for vegetables and beans as side dishes, as most starches and grains are fairly high on the glycemic index.

2. Eat fewer carbohydrates – If you do decide to eat a food with a high glycemic index, you can still minimize the blood glucose spike by consuming fewer carbohydrates at one time. One slice of white bread (a high glycemic index of 73) will still lead to a smaller glycemic excursion than two pieces of white bread.

3. Consider taking insulin earlier – It typically takes rapid-acting insulin (Novolog, Humalog, and Apidra) 60-90 minutes to peak, which can be slower than the rise in blood glucose after a meal. This is best illustrated in the experiment above with glucose tablets and three units of insulin. Over three hours, my blood glucose hardly changed from start (114 mg/dl) to finish (124 mg/dl), suggesting I took the right amount of insulin to cover the meal. However, my peak was still pretty high at 165 mg/dl, reflecting the mismatched rate of insulin absorption and post-meal glucose peaking. Had I taken my insulin 15-20 minutes prior to my meal, I would have seen a lower peak.

4. Take a walk! As I discussed in a previous Adam’s Corner, light walking lowers blood sugar more than you would expect – I found a drop of 1 mg/dl per minute of walking. There is lots of research to suggest that walking after meals really blunts the rise in post-meal blood glucose.

5. Test and Assess! Perhaps the best way to determine the post-meal impact of different carbohydrates is to test for yourself. Different foods affect different people in different ways, and the impact can vary drastically based on your exercise, stress levels, and amount of sleep.

Editor’s Note: Adam is a patient with diabetes and not a healthcare provider. Please consult with your doctor before making any changes to your diet, insulin, or medication regimen.

Adam is the co-managing editor of diaTribe and Chief of Staff at Close Concerns. He was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes at the age of 12 and has worn an insulin pump for the last 11 years and a CGM for the past three years. Most of Adam's writing for diaTribe focuses on diabetes technology, including blood glucose meters, CGMs, insulin pumps, and the artificial pancreas. Adam is passionate about exercise, nutrition, and wellness and spends his free time outdoors and staying active. He can be contacted at adam.brown@diatribe.org or @asbrown1 on twitter.