Fasting for Ramadan When You Have Diabetes

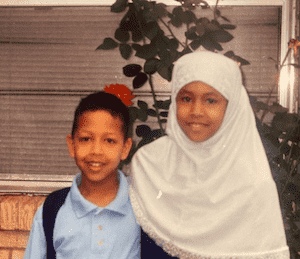

By Eritrea Mussa

Ramadan is an important religious holiday for Muslims. Because of its connection to fasting, it can pose some challenges to people with diabetes. diaTribe Social Media Manager Eritrea Mussa shares her experiences navigating Ramadan as a person living with diabetes.

Ramadan is an important religious holiday for Muslims. Because of its connection to fasting, it can pose some challenges to people with diabetes. diaTribe Social Media Manager Eritrea Mussa shares her experiences navigating Ramadan as a person living with diabetes.

Every year, millions of Muslims around the world observe the lunar cycle in preparation for Ramadan.

Ramadan is a time of fasting and growth when Muslims are required to refrain from eating and drinking from dawn to sunset each day. It can last up to 30 days depending on the sighting of the crescent moon. This year, Ramadan begins March 10 and lasts until April 9.

In Islam, Ramadan is also a time when Muslims are asked to consider their humanity and their impact. People are encouraged not only to abstain from eating and drinking but from other common behaviors, including gossiping, speaking negatively, or engaging in sexual relations. If you're a person living with diabetes, it can add an additional layer of challenges to a time when the main focus is growing together as a community or family unit.

As an American Muslim, my personal practices during Ramadan are pretty liberal. I was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes when I was 8 years old, too young to have begun fasting. Because abstaining from meals was impossible due to the insulin injections I had to take and the need to constantly monitor my blood sugar, my parents showed me how I could still observe Ramadan without fasting.

This primarily involves helping out my community and those around me who are fasting by preparing suhoor, the meal prior to the beginning of the fast, and iftar, the meal eaten at the end of the day to complete the fast.

Growing up, I attended Islamic School and would stay after school with Baba (my dad) for prayers. I’d help set up the women’s and men’s sections for the meals, counting napkins and forks to help do my part with chores around the masjid (mosque). I made setting up for iftar my thing. I ensured water cups and pitchers were full, extra cups and cutlery were available, and small styrofoam bowls of dates were always at the ready.

My Baba would also make sure I had the chance to talk to our lead sheik and Islamic studies teacher to clarify any questions I had about Ramadan. When I was younger, I found myself feeling sad and excluded from Ramadan in general because I wasn’t able to fast, until it was explained to me that Allah (SWT) makes allowances for people with disabilities or who take medication.

My health and my well-being came above all else in Islam, I was told. This gave my heart a bit of hope, feeling that my creator had considered my plight long before my existence, let alone my diagnosis.

Now, as an adult, a lot of my personal practices around Ramadan have much more to do with my community, family, and attempt to grow closer to my faith. I still do not fast food or water during Ramadan.

Diabetes stigma is prevalent in certain cultures

Others in the world have different understandings and practices. For Eman Diab, a 22-year-old Muslim woman in Egypt, Ramadan is also a time of year when she prioritizes growing closer to family. In 2022, Eman made the decision not to fast. In previous years, despite how it would impact her diabetes, she made the choice to fast as much as her body allowed.

This is partly because in Arab countries, having diabetes comes with stigma. And with an invisible condition like type 1 diabetes, it can be hard for some people to comprehend that a person can be young and healthy, but unable to properly fast. Having decided to not fast, Diab chose not to disclose that information to those around her because of this stigma; she also won't engage in eating or drinking water in public during Ramadan.

“Egyptians love food…this is a known fact,” Diab said.

“Egyptians love food…this is a known fact,” Diab said.

The challenge of carb-conscious eating during a holiday fast

She explained how in Egypt, food courses are broken up. First, the fast is broken with dates and milk, as well as dried fruits in natural juices. There are a plethora of drinks served at iftar, like Tamarind Hindi, which literally translates to Indian dates. Even in the appetizer, the carbs add up fast.

After the fast is broken, people pray and then have traditional soups. Typically, Arab soups such as Harrirah, lentil soup, and sambusas are common. After these dishes is the main course. The main course usually consists of a large protein, rice, and salad. An example would be a traditional Egyptian dish called Fattah, which is a combination of crispy bread, rice, lamb, vinegar, and tomato sauce. Following these two courses are the sweets.

Each year, new sweets and treats are shared such as Atayef and Mango Kanafe, an Arab treat made of phyllo dough, cheese, simple syrup, and in Diab’s case, mangoes. While delicious, these treats come with massive carb counts. It is common for families to indulge in a large iftar meal to break their fast, followed by mountains of sweets. Diab’s family includes two people with diabetes, herself and her sister. The two of them choose to eat fewer sweets, making sure they're not feeling too full after each meal.

Being too full during Ramadan “can make you lazy and miss the prayers,” Diab said.

Beyond the common notion that Ramadan centers around food, traditions in Egypt include many decorations and customs. Entire communities are decorated with beautiful colors, lanterns, and fabrics, making Ramadan one of the most special times of the year.

Beyond the common notion that Ramadan centers around food, traditions in Egypt include many decorations and customs. Entire communities are decorated with beautiful colors, lanterns, and fabrics, making Ramadan one of the most special times of the year.

Diab said her favorite part of Ramadan in Egypt is how the community comes together. The mosques get extremely full during this time of year and people will take to praying Taraweeh (a type of special prayer) in the streets.

“It’s so beautiful to see everyone, everywhere, praying together,” she said.

How some people with diabetes approach fasting during Ramadan

Mohammed Seyam, another person with diabetes who lives in Gaza City, Palestine, agrees with Diab that Egypt is a beautiful place to experience Ramadan. In Palestine, Seyam said the days during Ramadan can sometimes seem the same as any regular day. The big differences for him are the practices after iftar and suhoor. He said he notices many more people come to the mosque throughout the month. And much like Egypt, the entire city is decorated in a beautiful way with lanterns, lights, and festive decor.

There is something “special about everyone praying Fajr together” before beginning the fast each day, Seyam said. Fajr is the morning prayer that begins the fast.

“One of the big problems in Ramadan is that people eat a lot of sweets,” Seyam said. This is generally normal in Arab culture but is amplified during Ramadan. For Seyam, Ramadan is the month of spirituality and his ability to experience an elevated sense of community is beautiful. For him, the month doesn't center around food but more around faith and community.

As a person with diabetes who is also in medical school, Seyam explained that he understands how his body works and has an established plan to be able to fast during Ramadan.

As a person with diabetes who is also in medical school, Seyam explained that he understands how his body works and has an established plan to be able to fast during Ramadan.

To avoid hypoglycemia and to better manage his diabetes during Ramadan, Mohamad does his best to stick to a specific routine concerning what he eats and what he does throughout the day. He also takes naps during the sunlight hours and stays awake at night to ensure he is able to receive proper nutrition. He also does his best to refrain from long walks or too much movement to avoid potential lows.

A typical day will consist of waking for suhoor and fajr, where he loads up on protein and fats in attempts to keep his glucose level steady through the first few hours of fasting. He focuses on eggs for protein and lots of water to avoid dehydration throughout the day.

After suhoor, Seyam will typically sleep for about four to five hours. He starts his day a bit later during Ramadan, and finds himself testing his blood sugar much more during the fasting period. Prior to breaking the fast during iftar, he takes another long nap to get through the last bit of the fast. Although these practices may sound unconventional for some, Seyam enjoys fasting and is says that he is “up for the challenge.”

“Personally, I know that it is super risky to fast,” he said. “But I love to fast. I want to do it. I use the privilege that I have as a person with diabetes and an educated person in the medical field.”

How to avoid fasting in a way that is detrimental to your health

For those who can't fast, there are many ways to “join in and maybe try to experience fasting as people with diabetes,” Seyam said. For some, intermittent fasting can be an option, while continuing to drink water may be an option for others.

The bottom line on fasting during the holidays with diabetes

The important thing to consider during Ramadan as a person with diabetes is to do what you’re comfortable with and prioritize your health. Talk to your healthcare team openly about your practices during Ramadan, and work with them to come up with a plan for observing the season.

These days, during Ramadan, I try to make more of an effort to read the Quran, as well as spending time with my in-laws and my parents. The common Western understanding of Ramadan seems to center around food when in reality, it encompasses so much more. Ultimately to me, it is about growing together as a community in a way that honors my faith and makes sure that I am prioritizing my health.

Read more personal stories about diabetes here: