Elizabeth’s Secret

By James S. Hirsch

by james s. hirsch

Born in 1907, she was part of the American aristocracy, the daughter of one of the most prominent political figures in the first half of the 20th Century. But Elizabeth Evans Hughes achieved her own moment of fame, attracting international attention and, ultimately, writing one of the most poignant chapters in the history of diabetes. Her story – a remarkable brew of courage, triumph, secrecy, and shame – resonates to this day, and new details of her life emerge in a book that will be published later this year.

“Breakthrough: Elizabeth Hughes, the Discovery of Insulin, and the Making of a Medical Miracle,” by Thea Cooper and Arthur Ainsberg, captures the complex human drama of the teenage girl who was saved by insulin.* I wrote about Elizabeth in my own book on diabetes and interviewed two of her children.

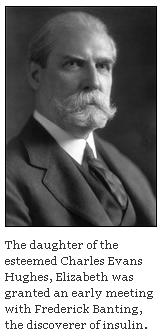

Elizabeth, even as a young girl, had a front-row seat to history. Her father, Charles Evans Hughes, was the governor of New York, and the family entertained America’s first couple, allowing President William Howard Taft to bounce Elizabeth on his ample knee. Hughes himself had few peers in public life: he was appointed to the US Supreme Court in 1910, was the Republican nominee for president in 1916, was Secretary of State in the 1920s, and returned to the Supreme Court, as chief justice, from 1930 to 1941.

The “starvation diet” radically restricted carbohydrates as the one method to deter fatally high blood sugar levels. The treatment was cruel, but death from starvation was considered more humane than death from ketoacidosis. Elizabeth was a “model patient” – she spent some time in a clinic in New Jersey but also, accompanied by a nurse, lived at home and traveled to upstate New York and Bermuda. (Her parents thought better weather would improve her health.) Her letters home conveyed the optimism of a teenage romantic while gushing over the splendor of a bald eagle or the enjoyment of night fishing. But when sugar appeared in her urine, she ate the equivalent of less than one piece of bread a day. On her fourteenth birthday, she received a hatbox covered with pink paper and fifteen candles, which she joyfully blew out.

By the summer of 1922, she had reached the outer limit of her life expectancy with diabetes – three years – and her end was coming near. Various illnesses (colds, an ulcerated tooth) had staggered her, she weighed less than 50 pounds, and her parents prepared to bury their second child in three years.

Then Elizabeth’s mother, Antoinette, read a news item about an experimental therapy being developed for diabetes, and on July 3, she wrote Frederick Banting at the University of Toronto to ask if he might help her daughter.

Banting was one of the principal researchers who had discovered insulin – the first patient had received an injection in January of 1922 – but the scientists had not yet found a way to consistently produce the drug. Their manufacturing methods were crude, and the insulin itself – made from the pancreatic glands of fetal calves – was impure. Supply was erratic. At one point in the spring of 1922, the Toronto team couldn’t produce any insulin at all. In the United States and Canada alone, thousands of diabetic patients needed this new treatment, but precious few had access to it.

In a return letter to Antoinette, Banting told her what he had to tell others in desperate need of a miracle: he could not see her daughter.

So Antoinette appealed to her husband, who was in his third year as secretary of state, and she asked that he intervene – a call to the president of the United States or the prime minister of Canada would surely do the trick. But Charles feared that using his position in that fashion was unethical.

“This is not really a state matter,” he said.

Antoinette begged him just to arrange a meeting between Elizabeth and Banting, and Banting could decide whether to give her the insulin.

“But the problem is one of shortage, is it not?” Charles said. “If so, then if Elizabeth receives insulin it may be at the cost of another child’s life.”

She began receiving two injections of insulin a day, and they were painful: the needles were long and thick, the brown, murky insulin was marred by contaminants, and Elizabeth’s hips and thighs were soon covered with welts. The new ones were purple, the older ones green fading to yellow. Some of the patients who had received the insulin had died, but in Elizabeth’s case, it worked. She increased her diet – white bread, corn, macaroni and cheese. She gained weight, two pounds a week, and had the strength to go to movies, concerts, trips to Niagara Falls, even outings with Banting, who took her to the lab where insulin was being made. She experienced the guilty pleasure of eating candy when her blood sugar was low.

Banting was obviously thrilled by Elizabeth’s recovery – perhaps the clearest indication yet that insulin could revive “the erstwhile dead.” He invited doctors from Canada and the United States to inspect her, and word of her miraculous “cure” was soon reported in newspapers across North America.

But the child herself loathed the attention. For one thing, she received letters from other diabetic children who were in need of insulin, and her heart ached for those who were denied. Elizabeth also hated the publicity. “Please don’t let on to a newspaper reporter!” she wrote to her mother. “Haven’t they been horrible though” with their intrusive coverage.

She left Toronto in December, without her nurse, and returned to her family. She continued her schooling, traveled to Europe in the summer, played basketball, swam, attended Brooklyn Dodger games, participated in student government, and learned to smoke and drink alcohol. She graduated from Barnard College in 1929.

Insulin was indeed one of the greatest breakthroughs in medical history, and now it had the ideal poster child – the beloved daughter of America’s top diplomat – to hail its triumph.

What she craved was normalcy, anonymity, a life without diabetes. She would always have diabetes, of course, but she could conspire to achieve the next best thing: she could hide her medical condition, lie about it, expunge it from the record, and lead a secret life as a diabetic. She may have been the world’s most famous insulin pioneer, but she spent the rest of her years trying to conceal the very ailment for which she was celebrated.

In 1930, she married William T. Gossett, a young lawyer, but she didn’t tell him about her diabetes until after they were engaged. A two-volume biography of Charles Evans Hughes was published in 1951, three years after his death; Elizabeth and the rest of the family cooperated on one condition: the author not mention her diabetes. In fact, Elizabeth deleted any reference to her disease from her father’s papers. She also destroyed any photographs taken during her illness. Even after she became involved in various philanthropic activities, she never gave any money or support to any diabetic charity.

She and her husband moved to Michigan, where he worked in the legal department for the Ford Motor Company, and Elizabeth raised three children, all born by caesarian section. She was the very picture of good heath, walking regularly, riding her bicycle, and gardening, but some routines puzzled the children. Each evening at 5:30, their mother would go into the bedroom, lock the door, and not return for several minutes. She never said what she did.

Elizabeth concealed her diabetes from her own children, hiding her insulin bottles, syringes, and testing supplies and never allowing them to watch her injections, which she took twice a day. The subterfuge created contradictions: she forbade cookies and other treats in the house, privately believing they would increase the risk of diabetes in her own children, but she herself kept hard candy in her purse.

Deception came in handy. When someone recognized her name and asked if she was that young girl who had been saved by insulin many years ago, she said no – that was my sister, Helen, who’s now dead.

“I so admired her for her being able to cope with this,” her son, Tom, told me, “but it wasn’t until later that I thought it was too bad she had to” maintain secrecy.

Her children suspect she simply wanted to live a “normal life” and not be treated any differently. It’s also likely that she wanted to purge the grim memories of her starvation years. She may also have feared that her illness would reflect badly on her family name. But “Breakthrough’s” authors suggest another reason for her cloak: “that her emancipation from the fatal destiny was, quite possibly, purchased at the expense of another child’s life.”

It was indeed a zero-sum game: Elizabeth’s receiving of insulin meant that – given the shortage of supply – some other diabetic child did not receive it, and Elizabeth surely understood that brutal algorithm. In one sense, she was the embodiment of misplaced diabetic shame – like thousands of others, she feared the stigma of this condition. But her heartbreaking secrecy, even to her own children, suggests that guilt complicated her burden.

In 1980, the medical historian Michael Bliss tracked down Elizabeth for his book on the discovery of insulin. She agreed to cooperate, on one condition: he could not use her real name, so he planned to call her “Katharine Lonsdale, the diabetic daughter of a prominent American political figure.”

The following year, after a trip to China, Elizabeth fell ill and was taken to the hospital with a blood sugar of 700. The doctors later discovered that she had suffered, fittingly enough, “silent heart attacks.” On April 25, 1981, after some 43,000 injections of insulin, she died at age 73.

Her obituaries included no reference to her diabetes. In life and in death, her secret was safe.