Behind bars, with diabetes

By James S. Hirsch

By James S. Hirsch

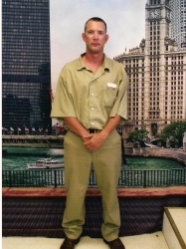

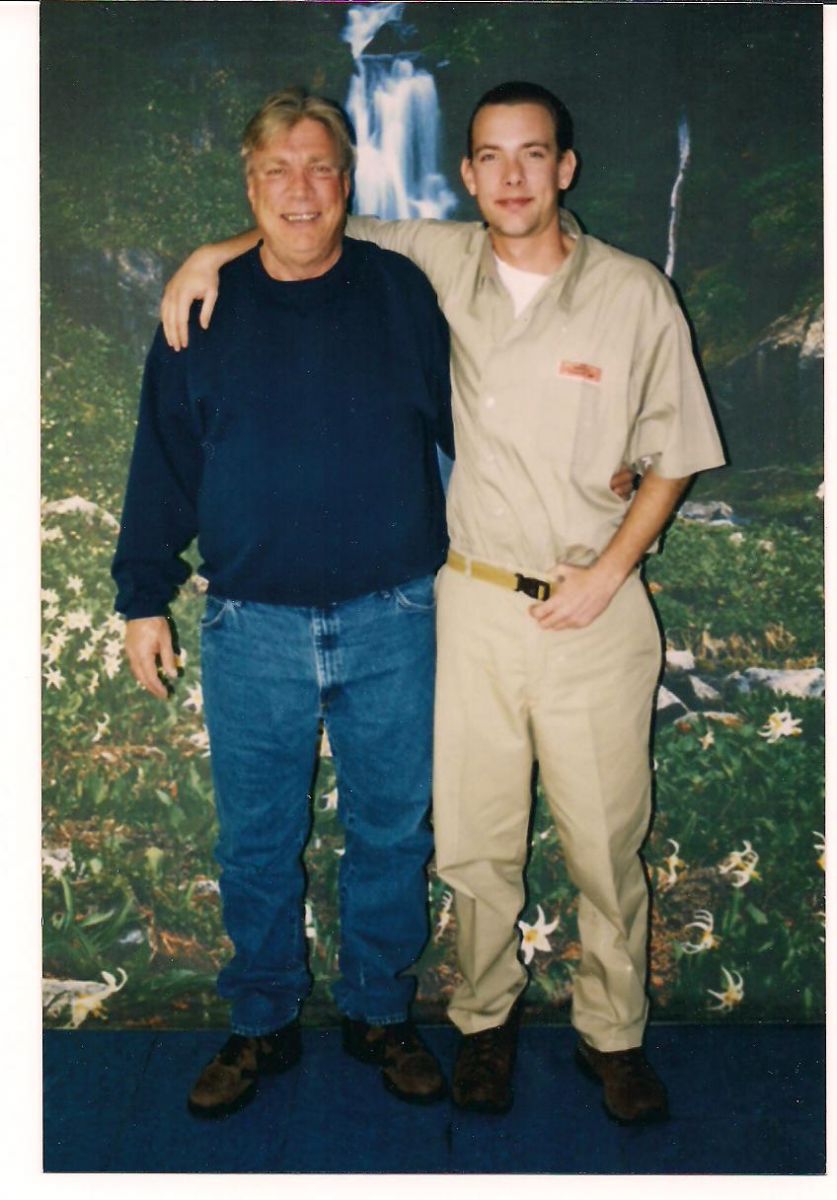

At first glance, James D. Ward is not the most sympathetic figure. In 2006, he pled guilty to “delivery of a controlled substance that resulted in a death.” The substance was heroin. He already had a criminal record – he’d been caught, according to his father, changing prices at a Wal-Mart earlier that year – and he was given a 15-year sentence for the drug crime. At age 25, he had already fathered four children with four different women.

But it’s also possible to see “Jay,” as he is known, as a kind of victim, or at least someone with a horrific run of bad luck. In 2005, he was diagnosed with testicular cancer, which was removed surgically. After the operation, he was prescribed painkillers, only to become addicted, which led him to his use of heroin, according to his father, James J. Ward.

After Jay was arrested on the drug charge, he was held in a jail in Plano, Texas. The first night he called his father and told him that his stomach was hurting. He was also thirsty and was having to go to the bathroom frequently. James J. Ward’s mother had type 1 diabetes, but he didn’t know the symptoms. Jay was taken to Parkland Hospital and given an X-ray, which came back negative, and he was returned to the jail. But his illness continued, including shortness of breath and vomiting. Days passed, until one night the Sergeant called an ambulance, and the paramedic who saw Jay had the good sense to test his blood sugar. It was 951.

Jay called his father each night, so when James didn’t hear from him, he called the Sergeant, who told him that his son had been taken to the Emergency Room. James dropped the receiver, and it was still off the hook when he returned two days later.

At the hospital, James saw his son in a diabetic coma. “They had a tube right down him,” he said. “I about died right there. The doctor wouldn’t tell me if he was going to live.”

The doctor later said that Jay had a 10 percent chance of surviving the night. He did, but now he had to manage his type 1 diabetes while in custody. His diagnosis did come with one saving grace: when he got out of the hospital, he was no longer addicted to heroin.

According to his father, Jay was innocent of the drug crime but was “sold out” by a public defender who convinced his son to plead guilty in order to receive a lesser sentence. Regardless, Jay was now facing 15 years in prison.

“I got cancer, I got diabetes, and I ended up in prison,” Jay told me in a recent telephone interview.

Unfortunately, his problems were just beginning.

What does it mean to have diabetes in prison? For starters, there are plenty of inmates with the disease. According to the ADA, of the more than 2 million people incarcerated in jails and prisons in the United States, nearly 80,000, or 4.8 percent, have type 1 or type 2 diabetes. That is somewhat below the prevalence rate of the general population, probably because the prison demographic is younger.

No prison will ever be known for excellent health care, but every prisoner is entitled to adequate health care – a Constitutional right under the Eighth Amendment’s ban against cruel and unusual punishment. What’s more, the Federal Bureau of Prisons has issued guidelines for the management of diabetes – type 1, type 2, and gestational – which are to be followed by each federal prison in America. The document, most recently updated in 2012, is 50 pages and quite thorough, covering everything from “Definite Indications for Insulin as Initial Therapy” to “Cardinal Signs of Periodontitis.” It also stipulates that frequent monitoring of blood glucose (three times a day) is optimal for a diabetic patient on insulin.

In other words, any federal prison that does what it’s supposed to do, in following its own guidelines, should provide adequate diabetic care.

But that hasn’t been the case for Jay Ward, who’s already been in six separate prisons in five years, in part because his father has complained, through letters and phone calls, that Jay has been receiving poor care at a particular institution and would fare better someplace else. Jay contracted hepatitis C, a viral infection affecting the liver, due to unsanitary conditions at a prison in Beaumont, Texas. He said he’s receiving no treatment for it because his current prison is waiting until his liver worsens. He suffers from painful diabetic neuropathy in his legs. While he has a glucose meter in his cell and tests his blood sugar five times a day, he cannot test for ketones. He’s had numerous hypoglycemic episodes, including one in which he came inside from the yard, reached his cell, and was addled for three hours. When he regained awareness, he tested his blood sugar and was 22. He drank a soda.

Jay is fortunate in one sense – through information sent to him by his father, he has educated himself about diabetes and understands the importance of tight control to reduce the risk of complications. That awareness motivates him. “My concern is that something bad will happen, like getting a limb cut off,” he said. (I had two 15-minute phone conversations with Jay.) His father sends him money to purchase healthier foods at the commissary, as the dining hall is a triumph on low-cost, high-carb offerings (rice, pasta, potatoes).

about diabetes and understands the importance of tight control to reduce the risk of complications. That awareness motivates him. “My concern is that something bad will happen, like getting a limb cut off,” he said. (I had two 15-minute phone conversations with Jay.) His father sends him money to purchase healthier foods at the commissary, as the dining hall is a triumph on low-cost, high-carb offerings (rice, pasta, potatoes).

Even those meals are better than others. Jay said that a friend of his worked in the kitchen at the prison in Butner, North Carolina, where Jay was incarcerated for three years, and the kitchen would receive boxes marked “Not Fit for Human Consumption.” It was supposed to go to animals.

Since August of last year, Jay has been at the medium-security prison in Leavenworth, Kansas. (He transferred from Butner so he could be closer to his family.) He cannot keep his insulin or syringes in his cell but must go to the health center. His problem is the schedule: he is forced to take his insulin injections several hours after his meals (the prison requires a nurse to give them to him), ensuring sharp blood sugar spikes several times a day. He eats breakfast at 6:30 a.m. but does not receive his morning injection until 8 a.m. (5 units of Regular; 20 units of NPH). He eats lunch at 11:30 a.m. but does not get his next shot until 3 p.m. (5 units of Regular), a full 3 ½ hours after his meal. This pattern repeats itself in the evening, when he eats supper at 5 p.m. but cannot take his insulin until 8 p.m. (5 Regular, 18 NPH).

This regimen does not conform with the Bureau of Prisons own guidelines, which describes short-acting insulin – such as Regular – as “pre-meal.” It also contravenes community standards for basic health care in diabetes; namely, that short-acting insulin should be given 15 to 30 minutes before a meal so it can “cover” or counteract the carbohydrates and allow the individual to maintain near-normal blood sugars.

By the time Jay can take his insulin, his blood sugars have usually spiked to 300 or 400, he said. “All you’re doing is playing catch up.” The prison doesn’t, as you might imagine, allow insulin analogs, so in addition to the awful timing, the poor stability of the insulin contributes to lots of glycemic variability.

The glycemic fluctuation, he said, depletes his energy, exacerbates his neuropathy, and has also caused his A1c to rise. It was 7.1 at his previous prison. Now it’s nearly 8.0 – though Jay said he’s never actually seen the results and isn’t certain that he’s receiving the correct information…

Jay said he’s formally appealed his insulin schedule to the warden and to the Federal Bureau of Prison’s North Central Regional Office, which oversees Leavenworth; the appeals have been turned down. He is now appealing to the Central Office in Washington, and if that fails, he will seek a transfer.

According to Jay, about 15 or 20 prisoners take insulin each day at Leavenworth, but he appears to be the only who’s protesting the schedule, perhaps because the other inmates don’t know better.

“Jay is in an institution that flatly refuses to accommodate his needs, and they admit it,” said Phillip Baker, a retired public health administrator in Austin, Texas, who has worked in prisons and now advocates for diabetic prisoners, including Jay. Baker said he spoke to the medical director at Leavenworth, and she told him that the prison would never change how it gives insulin. According to Baker, she also said that she wanted to put Jay on metformin – even though metformin is used exclusively for type 2 diabetes.

“There is a strong belief in prisons that health care is a privilege, and it can be yanked,” Baker said. “But that’s not the case. The felon is to be incarcerated but not mangled medically.”

I spoke to Tom Sheldrake, the public affairs officer at Leavenworth. I wanted to ask him about the medical care at the prison for Jay and other type 1 inmates. He said I needed to submit the questions in writing. I did so. I specifically asked why type 1 patients were given their short-acting insulin several hours after their meals; how often are diabetic inmates given medical exams; are they checked for diabetic complications; how often is their A1c tested; and are diabetic inmates given the “community standard” of care. I have not yet received a response.

James Ward, a truck driver who raised his son by himself, continues to be a tireless advocate, sending letters and emails and making calls to anyone who can help Jay. He asserts that, among the betrayals from the government, Jay’s plea agreement stipulated quality health care, which has not occurred. James takes obvious pride in his son. “I would like to see him leaving federal prison on his feet, not in a box,” he said.

Jay was sentenced in 2007, but he and his father both say that he will be released in 2019, which would make him 38 years old. A young man. In my two conversations with Jay, I didn’t have time to ask him why or how he got into prison, and I have no reason to pass judgment on him. The judicial system is already punishing him, but his diabetes should not represent a second punishment. If you believe in rehabilitation, or redemption, or just in basic decency, Jay deserves far, far better than what he’s gotten in prison.

As Jay said, “They didn’t commit me to death. I’m entitled to the same health care that they get on the street, but I’m getting well below that. I plan on getting out of here and not making any more mistakes.” Upon his release, James plans to obtain his personal training certification to help people with diabetes be more active.

You can help James by signing our petition to protest this unacceptable care for people with diabetes.